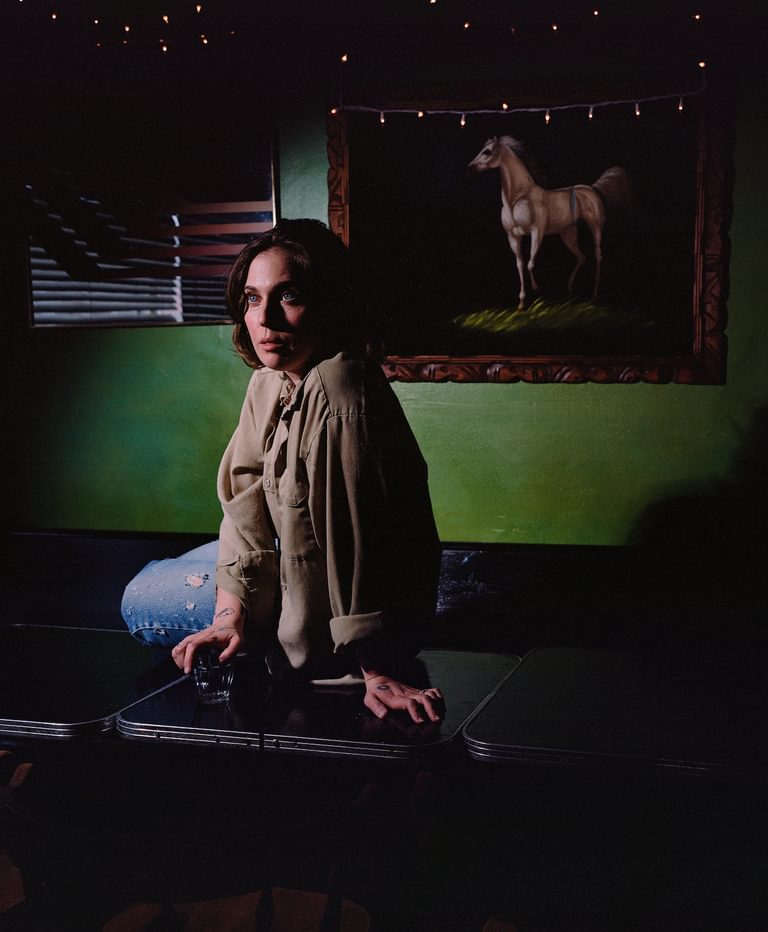

U.S. Girls turns inward

On the new U.S. Girls album Scratch It, Meg Remy dials down the politics to pick through inner turmoil and history against a backdrop of dusty, soulful numbers. But it doesn’t mean she’s not still thinking ahead, as she tells Sam Franzini.

Since forming U.S. Girls in 2007, Meg Remy has staked an increasingly impressive claim on cutting satires of contemporary American culture, societal rot, and misogyny through deep character work, disguised narratives, and, sometimes, just plain rage.

The women of 2015’s Half Free (her first for 4AD) were waiting, wondering, and lonely, while 2018’s In a Poem Unlimited and 2020’s Heavy Light seethed with stories of domestic abuse, environmental pollution, and the lunacy of capitalism. Even Barack Obama came under her fire on the scathing “M.A.H.” (aka “Mad as Hell”).

Given the increasingly hostile climate that has followed Donald Trump’s latest derailing of the country, it’s perhaps surprising that Scratch It – the ninth U.S. Girls album, out this week – is at once Remy’s most American and least overtly political record in a while. Instead, it turns its focus toward Meg Remy herself. “I feel that the only way to affect change, political or otherwise, on a larger scale, is working on yourself first and foremost,” she tells Best Fit from her studio in Toronto, a Canadian lilt in her voice whenever she asks you know? “I found it time and time again.”

Her husband says her previous records made her an exhibitionist, which she doesn’t deny. She was “writing from other people’s perspectives, or about large-scale systemic issues in a small way… I always like to share the hard lessons that I’ve learned.” But this time felt different. The most outwardly sociological song on Scratch It is an apology to Patti Smith for missing her set at a festival they played together. Perhaps second is “Firefly on the 4th of July”, a jaunty cover passed to her by the Russian songwriter Alex Lukashevsky about a nuclear bomb hitting Manhattan – though there is a slapstick comedy to the image of a firefly trying to compete with fireworks… trying to compete with a nuclear holocaust.

“There’s a lot of understandable anger right now,” Remy says about Scratch It’s self-analysis. “I think we’re all throwing a lot of facts at each other. You know when you’re talking to someone and you’re like, ‘Oh, you read The Guardian.’ I just wanted to come at [the record] from a place of empirical evidence, what I’ve experienced firsthand in my life that I can definitely speak on as a truth of mine. In turn, it’s political.”

It works. Made in Nashville in just ten days, the album is a complicated patchwork of emotions and stories, going from a friend’s death to a reworked hymn to alcoholism to nuclear apocalypse to grooving, as she defends James Brown’s thesis on Scratch It’s opening song: “Like James said, you gotta dance till you feel better.”

But the record isn’t without its stories or frustrations; Remy was distracted on “Dear Patti” because she was trying to keep her toddlers away from a lake. It was a complicated day, full of hierarchies – U.S. Girls opened for Patti Smith, who opened for The National. “Only two women on the stage that day,” she sings, the concreteness of two women being placed below an all-male band making way for overthinking and doubt. “We’re all musicians on that stage who have toured, struggled, dealt with shitty labels,” Remy says, but admits she still didn’t feel confident in approaching Smith. “There's so much in common and so much keeping you apart.”

“When you know your rank / And you got your file / So you just say in line / Dreaming of getting higher,” the song goes. “The only person I should really dissect in this is myself – the only one I can,” she says. “It felt like I was at a bit of a fault for going into a scenario assuming things. Especially coming in contact with power, [there’s] all of this fortune telling, ‘Maybe I’ll meet her, maybe we’ll play shows together.’ You don’t really do that if you’re going to the grocery store.”

Power is a complicated emotion for Remy: everyone’s got it, and it must be used carefully. “I have to constantly be checking myself that I have this power over [my children],” she says. “They’re learning from me, and I’m their main mimic.” But where she – and you and me – have no power is within the enormity of the world. Reading The Cancer Journals by Audre Lorde, she was struck by the idea, “If I am not scared of death, who can ever have power over me again?” It ties back into the current crisis, the cavalcade of terrible news and fascism and bigotry and greed. If the American president wants our attention, what’s more radical than turning our backs and focusing on ourselves? It might be the only true tool we have.

“I do think, yes, this energy we want to try and transform, shift, change, stop – it can kill you,” she says. “And they may want to kill us. But if we’re not scared of that death, what do they have over us? I don’t know, there’s no answer. We’re in such a dense knot, and it’s partially one we’ve created. I think that’s the hard part.”

“But I’m into now,” she continues. “I think it’s fascinating. I wouldn’t really want to be alive at another time. I’m so curious what’s gonna go down. I hope I get to see it. It doesn’t get more entertaining than this! [We have] the best book, best movie ever written. I’m up for it. I’m up for dying for it, too. And I will. We all will die for it. In order to have been a human on this planet, you die for the chance to live here and do this.”

I mention that this is something I’ve been thinking about, too – dating apps are ridiculous, and I’ve had to pivot and rethink with the drying up of paying journalism jobs. But it’s simply the era we live in, and there’s a beauty to being in the here and now. Remy’s musician friends are having similar conversations, too. “Make the most of it, and make what you want,” she says. “That’s what I think is really fascinating about now. We have so much technology and connection at our fingertips. We can rewrite with courage, with money and metrics not being the currencies we work in. If we could work on satisfaction and inspiration as the metrics, we could do fucking anything!”

It’s a jolt of optimism from someone who has been writing smouldering critiques for a decade, though 2018’s standout “Poem” echoes this line of thinking. Accordingly, Scratch It is unexpectedly lovely in an arms-behind-your-head, summery way, to be played while lying in the grass by a lake or on a long walk with no destination. Its grittiest moment comes right at the end, in a song inspired by a phone call with a former friend who cruelly dispensed some gardening advice. “You got no fruit,” Remy spits against guitars, one of the meekest yet cutting jabs of the year.

“Walking Song” is a reworked “sex-positive hymn” inspired by hookups disguised as nature breaks as pre-teens (“which was when I was my most promiscuous”). Here she tweaks the lyrics from the classic spiritual song “Just a Closer Walk with Thee”, abandoning the Christianity angle (“I could see someone getting mad at me for that”) yet keeping it in mind. “The closer I walk with Jesus,” she remembers, “I thought, ‘Oh man, Jesus was definitely into sex, no doubt.’” When in Nashville!

That’s not to say Scratch It is mostly playtime. The narrator of “Pay Streak”, written with Canadian roots musician Kim Beggs, takes a job waiting tables in Yukon, watching the gamblers and showgirls searching for enlightenment in the extreme pitch-black winters.

Elsewhere, "Emptying the Jimador” has the narrator in a stretch dress, shoe-less and downing tequila after a show. I say ‘narrator’ because, despite the record’s personal angle, Remy’s character work isn’t entirely dispensed with. “Never thought it would take so few pours to introduce me to the floor,” she sings.

The storytelling and personal narrative of Scratch It collide most effectively on “Bookends”, the album’s psychedelic 12-minute peak that ruminates on the death of her friend Riley Gale through a reading of John Carey’s Eyewitness to History, which collects firsthand accounts of civilisation’s biggest events. “This song’s like when they made sushi tacos,” Remy says. “Just so much going on.”

The book’s enormous scope, spanning the centuries between the death of Socrates to the bombing of Nagasaki, allowed for some out-of-date turns of phrase from the civilians who witnessed them. Remy started underlining them as she read, documenting each oddity, and quickly realised that the book was, at its base, about death. “I think death really makes art happen,” she says. “It’s something people want to document, and it pushes language. You’d think this ultimate mystery would make language be born to begin with, to try and explain what you’ve just seen.”

The scale of death once documented is nowhere near what we experience today, with the daily onslaught of social media and 24-hour news channels, and Remy was left wondering why Gale – this one person – still outweighed in her mind the victims of volcanic eruptions or the San Francisco earthquake. “70,000 men, why am I still wondering where Riley went?” she asks after the slow balladry of the song’s first half transforms into a jittery disco boogie.

"I was really in love with making something in a way that records used to be made"

She and Gale weren’t that close – they played a handful of shows together – but historicising him made her think about the effect we can have on each other’s lives, no matter how passing. “It’s like when you’re walking by a person asking for change and you don’t say anything,” she says. “You’re dehumanising them. Someone’s speaking to you and you’re ignoring them. How could that potentially shift, just by acknowledging their humanity?” The political in the personal, there again.

If Scratch It sounds weathered or worn-in, it both is and isn’t a product of circumstance. After a creatively invigorating set with an American band at an Arkansas music festival (where the Patti Smith story came from), she booked a Nashville studio for ten days, with no demos or ideas, both risky and guided. Some new textures came out of recording on 16-track tape, and the band played live with few cuts and little editing. “I was really in love with making something in a way that records used to be made,” she says, mentioning that her engineer urged her to leave false notes in favour of an emotional insight. “What matters more when you’re trying to convey something?”

If the harmonica and folky tuning didn’t give it away, Remy strived to make a Nashville record, merging the U.S. Girls brand with the history of the city’s extensive musical output. “Leaning into the pop culture, working within existing forms and trying to make them my own” is how she describes her process. “Trying to make something that only could’ve been made now, not a recreation of something or you could trick someone into sounding from 1969.”

In a way, the making of Scratch It has opened up new doors of creativity. At the top of our hour together, she mentions that she’s already starting on the next record. “It adds something that’s at my core,” she says when I ask what Scratch It brings to her discography. In wanting to make a Nashville record that pulls from her love of late ‘50s R&B, and achieving it, she says “My confidence really went up. I can totally hang.”

The stability of self-knowledge is freeing, and there was confirmation of that from 4AD, who agreed with Remy that there was no other option for a lead single other than the cinematic odyssey of “Bookends”. “I’m lucky I’m 40 years old,” she says. “They know me, I know them. They know I’m not a pop star.” Even the ten-day studio time came out of concrete limitations, with Remy being a full-time parent now. Recording so hastily, she realised, suits the way she likes to work. “It almost suits my performance style as well,” she says. “I’m not sure more time spent on something means it gets better.”

“I feel very certain I’m not done,” she adds when talking about what the album did for her. “The industry may say it’s done with me. I have no control over that. That could happen, the gas is out of the tank and I’m not making any more money, but I’m not out of ideas for music. I think I’m always gonna be making records even if there’s no money. I feel really fortified.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Patrick Wolf

Crying The Neck