Skin's Personal Best

With new album The Painful Truth welcoming in a revitalised Skunk Anansie, Alan Pedder looks back with Skin on how they got here and her five favourite songs from the past 30 years.

The thing about building a legacy is that someday you’ll have to reckon with it.

It’s easy to get caught up in the moment and lose sight of your intentions, but it’s when everything stops that the verdict comes in. Are you the artist you thought you’d be? Is your work still relevant, still adding something of value? If not, what are you doing? What can you change? Is there sense in carrying on?

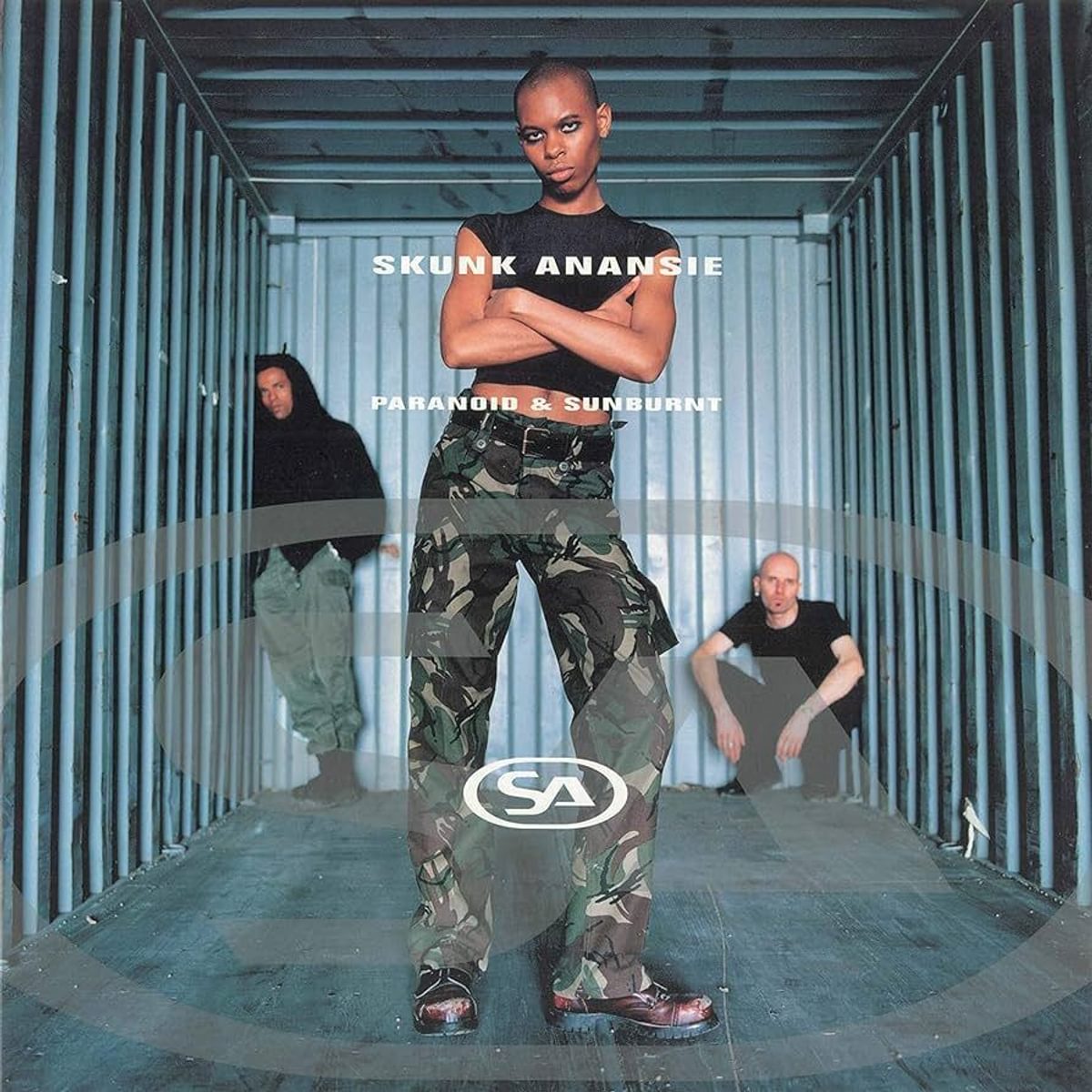

Those aren’t easy questions to sit with, but sooner or later they catch up with us all – demanding we look intently in the mirror and ask, what’s the painful truth? For Skin and her Skunk Anansie bandmates, that reckoning began to dawn five springtimes ago, at the start of the pandemic. The band were in the middle of celebrating 25 years since their debut album Paranoid & Sunburnt – a polemical combat-boot kick in the shins of the misogynistic, almost monocultural Britpop machine of the time – but with their anniversary tour scrapped and income drying up, a rethink was required.

Although they did resume the tour in 2022, it meant that with Paranoid & Sunburnt’s 30th anniversary approaching, it felt ridiculous to go out and pat themselves on the back again so soon. “We didn’t want it to seem like we were always looking backwards,” says Skin, “It’s not good enough for us to just go around the world every couple of years playing the old songs. I’m not disrespecting other bands that do it, because every band is different and deserves to do things in whatever way they choose. I strongly believe that. But, for us, it’s so important to have something new and exciting to play.”

The trouble is, the songs they’d been writing during the downtime of the pandemic just weren’t up to scratch. Add to that parenthood, the retirement of their longtime manager, and some serious health issues within the band, and the result was “a lot of analytical, scary, serious times” that forced them to really examine their self-worth, “as individuals, but mainly as a band.” “We did wonder if we should carry on,” she adds, “asking ourselves questions like ‘What is the point of us at this time?’ and ‘Do people really need to hear a new Skunk Anansie record? Does anyone even want to hear that?’”

Resolved to not put out another album unless they thought that it could “hit a nerve with people,” the band persevered with writing and rewriting, until the beginnings of something fresh slowly started to emerge. The turning point fully arrived while writing “An Artist is an Artist”, which became The Painful Truth’s explosive lead single and the benchmark against which everything else was judged. “I don’t think I’m being braggy or arrogant but from the beginning we were like, ‘That’s fucking good,’” Skin says, grinning. “It’s just a great song.”

With the notoriously discerning Dave Sitek (TV on the Radio, Maximum Balloon) coming on board as producer, revealing himself in the process as a big fan of the band, the song became something different still. “It was at that point that we knew that Skunk Anansie still had legs,” adds Skin. “We were a bit scared before it came out, because this song and this album are not your typical Skunk Anansie. It’s Skunk Anansie 3.0 – a brand new, fresh, and modern Skunk Anansie. It’s not a given that the music industry is going to give us that credit, but the reaction to the first song was amazing and very heartening.”

The need for perseverance didn’t stop once the songs were written, though. By all accounts, the recording sessions were fraught with insecurity and fear of fucking up – but that was part of the point. “We wanted to feel uncomfortable and unsure but just keep going, like fucking Dory,” she explains. “Just keep swimming until you get to a point where it feels okay.”

For Skin’s bandmates, who spent less time in the studio with Sitek than she did, there was a sense of terror that they couldn’t quite see the whole picture until the work was done. “It’s the first album we’ve made in bits and pieces, and the first time we’ve really written in the studio, so it was sometimes hard to get perspective in the moment. Perspective came over the months afterwards as we were finishing the songs off so we had that chance to again ask ourselves, what’s the painful truth? Are these good songs or not? Yeah, they are.”

Drawing on punk, dub, and electronic music, The Painful Truth benefits from the almost naivistic approach imposed on the band by Sitek’s rule that they couldn’t bring their own instruments to the studio – they had to make do with what was there. “That was quite hard for the boys, not to be able to play the instruments they love,” Skin says sympathetically. “But we really enjoyed fucking around with all the crazy gear that Dave has, trying to get a different sound. He had all these really bad instruments that actually sounded fantastic, because ultimately it’s not about the instruments it’s about the fingers on the fretboard. Anyway, I had a great mic so I was a bit like ‘Fuck you dudes, I’m happy.’”

With an album as evolved as The Painful Truth appearing 30 years into their career, Skin is fully aware that the band has no control over how version 3.0 will be received. She just hopes that Skunk Anansie gets to have a future beyond it. “I feel like we are very much aware that we’re at the point in our career where we can’t make an average record,” she says, summing up. “The lessons that we’ve learned over the past few years had to go into making a really great record, and that’s what I think we’ve done.”

With the focus quite rightly on looking forward, there’s still room for a little reflection when it comes to Skin’s own favourites from her back catalogue, as a solo artist as well as with Skunk Anansie. Choosing the songs that make up her Personal Best came pretty easily, she says, landing on three that she held dearly at the time and still enjoys now, bookended by two songs she feels are important to the journey of the Skunk Anansie sound.

“Little Baby Swastikkka” by Skunk Anansie (1995)

SKIN: I chose “Little Baby Swastikkka” because this song really defined the sound of early Skunk Anansie for me. There’s very little about this song that’s regular. There’s a little repetition in there, but it’s just a weird song that somehow really works.

It’s especially important to us because it was the very first song that anyone ever heard from Skunk. Jo Whiley and Steve Lamacq played it on their Evening Session show on Radio 1 one night, along with a few other songs, and asked their audience to vote for which track should be pressed up as a single. All the bands were unsigned, including us at that point, and “Little Baby Swastikkka” won. It was so successful that they had to print 2000 copies.

I’m using this almost comical baby voice on it because the song was inspired by a small swastika I had seen on a wall that looked like a four-year-old’s first try at drawing. It’s about the indoctrination of children into the kind of Nazi thinking that we are seeing now in certain places. Things haven’t really changed.

BEST FIT: It's weird that we're having this conversation the day after Elon Musk did his Hitler salute thing at Trump's inauguration.

Yeah. I watched it. I really try to avoid watching those guys, because it's not good for my blood pressure, but he did it twice, with the whole banging of the chest and that. He knew what he was doing. He knows who he's dog whistling to, and that's the world that we're in now. We have open fascism coming from someone who's in an American government. How did we get here?

Back in the ‘90s, people engaging in all the racial friction of that time were kind of ignorant of a lot of things, but people these days are inciting violence with full knowledge of what they are doing. But they don’t care because they feel so involved in the movement. They feel like America is with them. They feel like Germany is with them. They feel like France is with them. That’s a big difference from when I wrote the song. But they still go for the kids’ minds first, and that’s what “Little Baby Swastikkka” is really about.

Do you remember getting any backlash about the song at the time?

No, but I’m sure some Nazis were butt hurt about it. But, you know, that’s not a bad thing.

Do you have any stories about re-recording the song for Skunk Anansie’s debut album Paranoid & Sunburnt? I remember reading that you had to sort of trash the studio a bit to feel comfortable there.

Yeah, it was weird because we didn’t know how to perform without an audience. We were recording at a beautiful studio in a place called Great Linford Manor, but there was just no vibe to it. There was no audience, no reaction, and we had no idea how to record. So what we ended up doing was to make the studio look like a war zone, to create an atmosphere that could be conducive to practice, to writing, and to great performances.

I did my vocals in some kind of little hut and scribbled out all my feelings on the inside of it, trying to sort of fabricate the reaction of a live audience – and it actually worked. I kind of got into it, although it was pretty nerve wracking. I had a bit of a mental breakdown halfway through, but then I built myself back up. Sometimes you have to break yourself down to come back stronger, you know?

In the press release for “An Artist is an Artist”, the writer made a connection between the confrontational nature of that song and “Little Baby Swastikkka”. What’s your take on that?

Well, I think there's always going to be a volcanic side to me. I'm always going to be anti-Nazi. I'm always going to be a little bit incendiary. Whether I like it or not.

“Carmen Queasy” by Maxim feat. Skin (2000)

SKIN: Maxim is someone whom I love. He’s one of my favourite people. We came up in the industry at roughly the same time, and The Prodigy loved us. We were such fans of each other’s bands. They had us support them a lot, and we’d hang out backstage a bit at festivals too. They actually sampled our song “Selling Jesus” in a track of theirs [“Serial Thrilla”], which was really nice.

I remember going to his house and being amazed that he had a games room with all these statues around the pool table in full coats of armour, from different periods of time in history. I’d seen them in museums but I’d never seen them in somebody’s house before. He had a little studio next door so I turned up with all these ideas and verses to fit the piece of music that he’d given me and we just constructed the song there and then together.

I think “Carmen Queasy” is probably the most successful collaboration that I’ve done. The song is about having to put forward this fake kind of character and be somebody else in order to be successful. It’s partly about someone I knew who was pretending to not be gay, but more generally it’s about having to change yourself to suit other people and how that can make you feel calm and queasy inside. So ‘Carmen Queasy’ became the name for that character, in a sense.

I love that insight, because the lyrics are quite open to a lot of different interpretations.

Yeah, it has definitely been taken in different ways, and that often happens with songs once you put them out. People have come up to me and talked about a particular song, saying “Oh, I like that you wrote about blah blah blah,” and sometimes I'm like, “Huh, it's interesting that that’s what you got out of it…”

But I realised a long time ago that you can't force people to find the same meanings in a song. Once a song is out there in the ether it doesn't belong to you anymore, on a spiritual level. You've just got to let people see whatever they see in the songs and be happy about it.

This song somehow escaped me in 2000 so it’s been really interesting to read people’s takes on it. There’s one argument for it being about the dark side of the industry, which, you know, still resonates 25 years later. What’s really changed?

Not a lot. It’s actually got worse. It’s worse because most people don't earn money from making records anymore, because record companies just keep almost everything they get paid by streaming companies. They keep it for themselves and don’t even pass on a set percentage, and I don’t understand how that is legal.

“The Trouble With Me” by Skin (2003)

SKIN: This is one of my favourite songs I've ever written and it’s probably one of the most unsung too. Almost nobody knows about it. I think it’s a really good song – logically, lyrically – and I feel like if someone like Taylor Swift or whoever would cover it and do a bigger version, it could be huge. I love the way I sang it but the production is quite minimal. I think there's a fantastic song under there. Yeah, I’m bigging up one of my own songs, but I really do love it.

BEST FIT: That’s what we’re here for! Do you have a favourite lyric from the track?

It has to be “The trouble with me is my troubles with you.” I really love that because it’s so simple and so honest.

It was kind of a crazy time when I was making that album, in 2002–2003. Skunk had split up and I was living abroad. I’d had this relationship that was very poignant and the album’s called Fleshwounds because each of the songs on it felt like a little cut. The kind of cuts that you recover from but you definitely got wounded, you know? So that’s what those songs were about it, and that inspired the mellow sound of the album too.

“The Trouble with Me” is probably the best song on it, in my opinion. A lot of people love “Faithfulness”, which is the first track on the album, but “The Trouble with Me” was my thing. Lyrically, it’s quite vicious, and there were a lot of stabs going on in that album in general. But the thing is, if you sing those harsh words sweetly, people don’t notice as much. And, personally, I always love the juxtaposition of a very dark lyric with a sweet, sing-song melody.

What do you remember about the recording of the song?

I recorded this one in Belgium with David Kosten [aka DJ and producer Faultline], who had made some great records. We wouldn’t start in the studio until midday, so I would spend my mornings taking driving lessons as I wasn’t able to drive at that time. Then, when I got as far as I could with that, because I couldn’t take my test in Belgium, I moved on to motorbike lessons. There was nothing else to do in the town that we were recording in. I wanted to take helicopter lessons, but it was two or three hours each way to get there, so a bit too far. I’ve still never learnt to fly a helicopter, but I did buy a motorbike and that was a lot of fun.

“Purple” by Skin (2006)

SKIN: I love the melody to “Purple”. It’s kind of like a marching song. Again, it’s sort of about lost love. There are a couple of those songs on Fake Chemical State that are very much with the vibe of “but is she as good as I am?” – a bit mean and dark, but honest. I think the lyric “She won't go where I / I would go for you / I’d curse my heart for you” is a particularly lovely dark line of thought, and there’s a little bit of a musical trick to the way it is repeated in the song.

I co-wrote this one with Gary Clark [of ‘90s trio Transister] at my house in Ibiza, where I was living after being in the south of France for a while. I think it’s a beautiful little song. It was very popular in Italy. It was a hit there, and I’m quite proud of that. Italians just love this song!

BEST FIT: Skunk Anansie has always been pretty popular in Italy, if I remember rightly.

Yeah, and I think it was really important for us, in the early years, to get out of the UK to the rest of Europe. The one piece of advice I always give to a new band is “Be big somewhere.” It doesn't matter where it is, just be big. Just have one country where you're massive, because that will last you forever.

We were starting to think about getting the band back together around that time, in late 2006. I had been kind of wandering the planet, living in different places, but by the time I came to the end of making Fake Chemical State I knew it was time for me to go back home. I wanted to be back on solid ground and write with the boys, and to experience what it’s like to be in a rock band again.

“Lost And Found” by Skunk Anansie (2025)

SKIN: This is a very, very different song for us. It came out of something that Dave Sitek had written that I loved and wanted to use for the album. I was enchanted by the beginning and could hear myself on it, and then we worked together on some other bits to make it more Skunk and to get the vibe of me on there. It’s a song about seeing yourself as being lost in a desert and trying to get back to some kind of normality. It evokes a feeling of desperately wanting to get back to reality, hiding from the sun.

BEST FIT: It’s definitely different, and it’s quite a bold choice for a single as it’s not the most immediate radio song with the long a cappella opening.

Exactly, yeah. We wanted to take some risks and see what worked, and I think it really worked for this song to just take everything away at the beginning. There’s another song on the album that starts in a similar way, because we just loved it so much, but then we had to make sure they weren’t next to each other in the tracklist.

“Lost & Found”, for me, is a musical statement. It’s pretty complicated in terms of structure. Nothing repeats in exactly the same way. It sounds like it’s repeating itself but it actually doesn’t, and I love that about it. I love that on this album there are certain songs that, structurally, go very much against the grain of pop writing but they just work. I don’t think it’s wrong to want people to have to stretch themselves a bit to get into something. Too much these days I based around everything being easy, but I think making things not so easy and complicated is actually more interesting.

That ties in nicely with what your bandmate Cass said about the album, that it’s the first time Skunk Anansie have made an album that has given him goosebumps when listening back to it.

Yeah, and I feel the same way. I really love this album and feel like it’s the best one we’ve ever made.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex