The Movie Geek

Cinema was the first love of Bastille's Dan Smith and remains central to his creative approach. Writing for Best Fit he explains why films matter to him.

Growing up, my relationship with film was probably what most other musicians have with music. I loved making music, it was always something I did for fun and kept to myself, but film was my primary obsession.

My real passion for cinema began when I was ten. I remember watching a horror film when I was staying at a friend's house, and how exciting and transgressive it felt to be watching something that was meant to be unsuitable for me. I guess there’s something about being a kid and doing something you’re not meant to do that made it more thrilling. I also think when you’re younger and madly curious it’s easier to obsess over things.

The film was Wes Craven's Scream (1996) and it opened my eyes to slasher movies which led to an initial fascination with the horror genre. Scream is a satire in itself and the references it makes led me back through a genre my little mind wanted to learn more and more about - this mad American world with its rules and cliches. Scream’s director Wes Craven also directed A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) which detailed the disturbing escapades of Freddie Kruger and spawned many sequels. As a kid discovering whole franchises retrospectively like this felt like discovering the entire back catalogue of a band - like, say, The Beatles - long after they’ve broken up. It’s impossible to ever really un-know a legacy, and you can only really read about - and try to imagine - the context into which it was released at the time. Horror was a genre that was brimming with franchises, from the Halloween films to Friday the 13ths.

I devoured loads of films as I explored everything I could get access to at that age - from the mainstream horror films of the day right back in time through the classics. Watching and reading about Psycho (1960) was my gateway to the fascinating world of Alfred Hitchcock, his sizeable back catalogue of films and his pioneering knack for marketing them ingeniously. Jaws (1975) took me to Spielberg and Alien (1979) to Ridley Scott.

I also found myself fascinated by Japanese Horror, and then discovered Dario Argento and the Italian ‘giallo’ genre that he pioneered. Argento’s films turned horror movies into operatic masterpieces; his films were brightly colourful, stylised and visually bold. It fascinated me to learn that he recorded no audio on set as an international cast all delivered lines in their own languages, only to be collectively overdubbed afterwards.

I’m sure my parents were absolutely thrilled that I was so passionate about horror films but it eventually subsided and I like to think they’re probably relieved that I ended up in a band and not as a serial killer.

One of the more conventionally respected films that this interest in horror led me to was The Shining (1980). I was given a Kubrick box set for Christmas one year, and after everyone had gone to bed on Christmas night I watched The Shining by myself, from midnight until 2am. Suffice to say I was terrified and my little mind was blown by the countless iconic scenes and images that are now so famous in popular culture. It’s a great example of Kubrick choosing to work in a genre for the first time, and in the process making something that was both mainstream and artful, whilst also being hugely influential and iconic. It led me on a journey through all of Kubrick’s films. It was fascinating to look at the arc of his filmmaking and all that he achieved as he moved from genre to genre whilst always making films that were very much his own.

I was given a Kubrick box set for Christmas one year, and after everyone had gone to bed on Christmas night I watched The Shining by myself, from midnight until 2am.

I was really interested in A Clockwork Orange (1971), both in looking at how he’d chosen to adapt it for the screen, and also because of the controversy it caused when it was released. It’s so interesting to think back to a time when a film could provoke such a huge uproar and be pulled from cinemas by the director himself. It was kept from consumption in the UK for 27 years.

As part of my teenage exploration of the darker and weirder side of cinema, I started reading about David Lynch. When I was 15 he had a new film coming out that I became fascinated by: Mulholland Drive (2001). It was the first time I got to see a Lynch movie on the big screen and I went to a small art house cinema in London to watch it with my Dad (which, as a teenager I seem to remember felt a bit awkward during certain scenes).

Mulholland Drive is an incredible film to watch for the first time. It’s filled with beautiful, mysterious scenes and surreal images. It’s kind of mesmerising but also hugely confusing, and as my father and I walked out of the cinema neither of us really knew what to make of it - which I guess is kind of the point. We spent the journey home trying to piece together the narrative and figure out what we’d just watched. I loved how much the film expected of its audience: you have to engage and impose on it and almost help construct the narrative within the dream logic. It made me want to chat to people about it and led me online to find out what other people’s theories about the film were.

The Internet was an amazing tool for finding out about both old classics and leading me to new ones. I loved coming across new films that nobody had heard of yet. One of these films was Donnie Darko (2001) which I’d read about loads but had no theatrical release scheduled in the UK back then. I had to track down a DVD of it from the US, and I had it for about a year and half before it came out here in the UK. I remember eulogising about this hidden gem and making my mates at school watch it. I think there’s something about it that really speaks to teenagers. Richard Kelly struck such a chord with that film, especially with the use of ‘80s music and old songs. Kelly very cleverly makes things intense - there’s this emo moodiness that’s quite knowing.

When Donnie Darko finally came out in the UK, I went to see it at a tiny art house cinema with mates who also loved it but I pretty much knew the film off by heart at that point. It was such an amazing experience to have this thing that was such a classic in my head, finally get its day on the big screen. I'd been the one showing Donnie Darko to other people for ages, but when it eventually hit this mainstream nadir it no longer felt like the same film.

I think people have similar experiences with new bands who feel like their little secret - and then the minute everyone seems to love them, it’s hard to maintain that obsessive relationship because they almost feel tarnished by it.

Donnie Darko is much more narratively comprehensible than, say, Mulholland Drive but you have still have to really engage to find the meaning in it. Maybe it’s because adult life is way busier than school life - or maybe my attention span has shrunk - but in my pre-Uni years I could obsessively watch films I loved over and over again and get something different from them every time. Nowadays I always feel the growing realisation that there is just too much to see and not as much time to see it all. As a result, I find myself leaning towards things I’ve never seen rather than repeatedly pouring over older things.

Maybe I’ve lost that childish obsessiveness I had, or maybe it’s a slightly sad sea change in my mentality.

When I was a kid I wanted to be a director or an editor, but I slowly realised that I was always more of a fan than a filmmaker. After years of geeking out on films at school, I went on to study English Literature at university and loved the fact that my course seemed very open to what the definition of a ’text’ was. One of the last essays I wrote for my degree was on representations of autism in literature, and my main ‘text’ was the 1988 Bruce Willis film Mercury Rising. The film’s representation of autism is pretty narrow and unrealistic, and it was interesting to see how difficult it can be to write learning difficulties or mental health storylines into film narratives. They won’t cooperate with received Hollywood structures in which things often have to be wrapped up and resolved. I remember my lecturer was really bothered by the unhelpful and unrealistic frequency with which people on the autistic spectrum were portrayed with savant abilities (in films like Rain Man from 1998, for example). He felt it was a misrepresentation as it implied that all people with autism had these abilities, whilst generally using the condition as a plot device.

When I studied Shakespeare I chose to look at the many ways his plays had been adapted onto screen. There were loads of brilliant interpretations, but a fascinating and striking modern example was Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet (1996). It had a hugely appealing mainstream quality and felt more like an improvisational riff on the text, taking in so many pop culture references via Luhrmann’s amazing over-the-top operatic style. It’s a great example of film as mixed-media format where it’s as much about cinematography as it is about the narrative or words or the music that’s used. And this film in particular has a madly eclectic soundtrack that introduced me (when I first watched it as a kid) to loads of bands and songs I love.

School is really this mad, weird jumble of things - much like life... a cross-pollination of characters and personalities and events and happenings.

Last year I became obsessed with Freaks and Geeks (1999). I think it’s the most brilliant portrayal of being a teenager and at school. It ignores most of the Hollywood cliches about what it is to be young. From a British perspective, there’s a perception of American youth that we had when we were younger - you’d be totally forgiven for assuming everyone was either a jock or a geek or a band kid or whatever. But school is really this mad, weird jumble of things - much like life. It’s a cross-pollination of characters and personalities and events and happenings. People from different groups do go out with each other and as much as you don’t want your relationship with your parents to matter, it’s as important as the ones you have with your friends. Freaks and Geeks quite realistically, warmly and unglamorously portrays all those things.

There was a quote from one episode that we wanted to use on Wild World, our new album, in a song called “Snakes”. The quote “come on boys, let’s go tear this mother DOWN”, is meant to represent a moment of complete hedonistic abandon and we tried to clear it through official channels. We discovered that the actor who says the line had sadly died some years ago and we had a bit of trouble tracking down his estate. In the end we had to slightly re-write and re-record the line, but hopefully the spirit of the show is still detectable in there.

Putting samples from movies into our songs is something that we started doing on our first mixtape Other People’s Heartache. Our mixtapes started life with a cover that we used to play of “What Would You Do?” by City High, back when we only had about six songs we could play live. We needed something to fill out the set and it was a song that I remembered affectionately from when I was a kid. Whenever we played it people would find themselves singing along and trying to figure out where they knew it from. The life described in that song - stripping to earn money for your child - felt quite far from our lives as Londoners in our twenties. It’s such a sad song but it’s presented in such an upbeat R&B way, and I always thought there was something incongruous in that. We thought it would be interesting to re-represent it and I loved that process of re-imagining someone else’s work. We recorded the cover and put it online and it grew a life of its own. Through blogs and hype machine, it brought a whole new audience to our young band.

We decided to make a whole mixtape, inspired by the free albums of Frank Ocean and The Weeknd, and set out to record it as an imagined soundtrack to a film that didn’t exist. It opens with Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” (1936) which soundtracks Platoon (1986). Rather than doing a strings version, we just layered up my vocals loads into a disembodied choir of me, then using quotes from Platoon to segue into a bombastic version of Haddaway’s “What is Love”. They were so much fun to make alongside our first album, and they allowed us to experiment with production and sound design, using covers, mashups and samples to create a mad sense of present and past whilst segueing between songs and ideas. We took inspiration from Quentin Tarantino’s brilliantly curated soundtracks which not only uncover a host of brilliant old songs, but also incorporate dialogue from the films.

The Other People’s Heartache mixtapes are also a way for us to nod affectionately towards stuff we loved or remembered fondly. We did a version of TLC’s "No Scrubs" which we completely rearranged using the guitar riff from The XX’s “Angels” and a massive string arrangement to make it this big, epic thing. We used quotes from Psycho, assuming Norman Bates was a scrub because he lived at home with his mum. They’re innately tongue in cheek, but we took the process of making them pretty seriously and had so much fun doing so. <>Our use of ‘90s dance music in parts of the mixtapes was about reimagining these (in my eyes) sometimes underappreciated anthems that were amazing and often lyrically heartbreaking in their own right. I’ve always had a real interest in music and films that I see as overlooked classics.

The mixtapes were also a way for me to align all these loves of mine. In reality, as much as I obsessed over films I was always too lazy to actually go out and film things or direct my own little home movies - I much preferred analysing and, after a while, editing other people’s stuff. When it came to making a video for our first single “Flaws”, we had a budget of absolutely zero, so I thought it would be interesting to re-edit Terrence Mallick’s Badlands (1973) into a music video. As with all of Malick’s stuff, every frame is like a beautiful photograph or a painting, but the film is ultimately quite dark. Our song, however, was an upbeat little tune, so with the video I wanted to re-frame some of these amazing images from this film I loved and position them in a more optimistic light. I remember the excitement of seeing this video I’d put together rack up hundreds of thousands of views online. We were unsigned at the time, and a bit like with our mixtapes, our eventual record label wanted nothing to do with the video on account of the liberal attitude we’d taken to ‘borrowing’ other people’s work. Suffice to say none of them exist via our official Bastille channels anymore.

As much as I obsessed over films I was always too lazy to actually go out and film things or direct my own little home movies...

My Twitter account, much like this rambling article, is basically me talking about films and other people’s music that I love. When I was being asked about our first album I found it quite uncomfortable talking about myself and the music we’d made, so I loved being able to divert interviews onto my obsession with David Lynch and Twin Peaks (1990). Having a song called “Laura Palmer” often allowed me to just geek out on Lynch as a welcome deflection. I know the show has had a huge resurgence in the last few years, but at the time it was really satisfying hearing from a lot of our fans that they’d been turned onto Lynch and Twin Peaks because of that song and my incessant babbling about him and his work. Much like with Donnie Darko years before, when I discovered the series it was only available via a DVD from America. I eulogised about it and tried to convert all my mates into fans.

When I was at University in Leeds, I wrote about film and music for our university newspaper. I heard about an exhibition David Lynch had put in Paris called The Air Is On Fire (2007) and decided to go and see it under the guise of writing about it for the paper. It was a selection of paintings, video work, photographs and mixed media and as a huge Lynch fan I wanted to make this mini-pilgrimage to see some of his work. It was at the Fondation Cartier pour l'Art Contemporain, this really amazing box-like modern art gallery made largely of glass. For the exhibition, there were red and blue heavyweight velvet curtains hanging everywhere and one room consisted of his notes, drawings and doodles from throughout the years meticulously presented across all the walls. Some of them were sketches done on post-it notes or pages from his screenplays. It felt almost like a window into the inner workings of his mind and I remember thinking how amazing it was to have access to those things.

A couple of years ago, when we were playing some gigs in Paris and had a night off, we managed to visit Club Silencio, the nightclub Lynch designed and opened there. Named after a club in Mulholland Drive, it is a typically Lynchian environment set several stories underground, with a huge amount of thought put into all the little details of every room. Lynch, an avid smoker, had made an indoor smoking space that was like a surreal forest with cigarette smoke used to create atmospheric myst. Elsewhere, rooms were lined with logs, books, and gold leaf in knowing nods towards the aesthetic he’s constructed across all his films. I’ve always thought of him as a brilliant example of a modern day creative who has forged a career out of his own total individuality. Alongside the club and the exhibitions he creates, Lynch has his own charitable foundation, he's written books on meditation, and let’s not forget that he’s responsible for some of the greatest films in the history of cinema and one of the most influential television shows. And two albums.

Remixing someone else’s work involves a fair amount of destroying what they’d originally made so it’s always interesting to see how people react to your take on things.

Rob Da Bank who runs Sunday Best Recordings asked me to do a remix of a track from Lynch's second album The Big Dream. The song we chose to remix, “Are You Sure”, is the most pop-structured song on that record and for the remix we imagined David Lynch floating through space in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)-style, so we made this big, lush, choral musical environment for his voice to sit in, and laced the song with theramin solos to hammer home the outer space vibes. Emailing the remix over to them when we’d finished it felt pretty nerve-wracking. As you can probably tell, I hold him in quite high esteem and was nervous about what he’d think. Remixing someone else’s work involves a fair amount of destroying what they’d originally made so it’s always interesting to see how people react to your take on things. It transpired that him and his team loved the remix and said we should let them know when we were next in LA so we could pay him a visit. Of all the outcomes I’d imagined that one definitely wasn’t in there.

The next time we were in LA happened to be when we were doing our first ever show in the US in 2014, and I was invited to his house and studio in the Hollywood Hills. I had absolutely no idea what to expect from the experience. I’ve watched interviews where he’s been very outspoken, and some where he’s been borderline uncooperative with the wants of the interviewer when he's being challenged on an intellectual level about his films - so I was unsure of what he would be like in person. It's easy with people who are famed for a certain thing to box them into that one thing, which is obviously very short-sighted but I think people are often guilty of doing it.

His house/studio was like something out of Lost Highway (1997). The door opened into this cinema-screening-room-come-recording studio and Lynch walked across the room in overalls splattered in paint and said “Hello Dan!” with a warm smile while my stomach nearly fell out of my feet. He brewed some of his own David Lynch Coffee (oh look, there’s another thing the guy makes) and we hung out for a couple of hours. A lot of creative people love to talk about themselves a lot, but he was incredibly interested about the band and our creative process and was generally an incredibly warm and friendly guy.

He asked what my favourite gig of ours had been. We'd just played Shepherd's Bush Empire for the first time so I told him about that and his face sparked up in curiosity. “Is there a public toilet in Shepherd's Bush?”, he asked, which would have seemed like a pretty weird question had I not known exactly what he was talking about. I knew it because it what was an old Edwardian toilet had been turned into a gig venue called Ginglik where I used to play solo shows before we started Bastille. David then went on to tell me about how they’d shot a bunch of scenes for The Elephant Man (1980) in that toilet, and I guess I really enjoyed having this vague thing in common despite our very different lives.

We do most of our recording in a small windowless room underneath an estate in South London, and I think the limitations of the space kind of forces us to use our imagination.

Because our music started life on the laptop in my bedroom, it was always about the use of imagination and thinking outwards. We do most of our recording in a small windowless room underneath an estate in South London, and I think the limitations of the space kind of forces us to use our imagination. For me, being a 'bedroom artist' was always about not having much to work with but using what you have to try and create something bigger. Sonically it meant layering up vocals and strings to make them sound big and cinematic. The desire to make every song sound different to the others came from that culture of listening to soundtracks and loving how each song takes you to a different place and make you think of a different thing.

When I'm writing, a lot of the songs are monologues or dialogues that I'm imagining as scenes in my head. And then it's just about creating the atmosphere around it. On albums - and especially on this new record - it's about wanting to create a diverse series of moods and tones and that feeling like a series of scenes, an evolving narrative where you're not sure what turn it will take next.

I'm really drawn to podcasts at the moment and what I loved about Serial was that you only experience the visual truth through the sound. It completely relies on the listener bringing their visual imagination to the experience. Even though I can talk to my friends about Serial and even though we’ve listened to exactly the same thing, the events as they see them in their heads are inevitably different to mine. That’s what I hope people get from our songs too. We try to make our music as visual as possible, but I always love to hear different people's interpretations and understanding of the songs.

A lot of our videos are quite weird and confusing, and in our own little way I hope that people have to bring something to the experience and interpret them.

I always have a strong visual in my mind when writing and putting together our songs, but when it comes to making videos for them we never try to articulate that image. I’d always rather try to make something entirely different to the initial idea and have music videos that are companion pieces to, or re-interpretations of, the songs. Ever since our bastardised version of Badlands, I’ve always felt so lucky to have the opportunity to make videos and approach them like little mini-movies. A lot of our videos are quite weird and confusing, and in our own little way I hope that people have to bring something to the experience and interpret them. I’m always keen to have strong and striking imagery running throughout them too. As someone who isn't very comfortable on stage it's been amazing to be able to incorporate all the visuals we’ve created into our live shows. It's been really nice recutting and our videos and using b-roll footage from the shoots to help highlight the moods in songs when we play them live.

Maybe the whole process is just an opportunity to scratch that wannabe-filmmaker itch of mine.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Maria Chiara Argirò

Closer

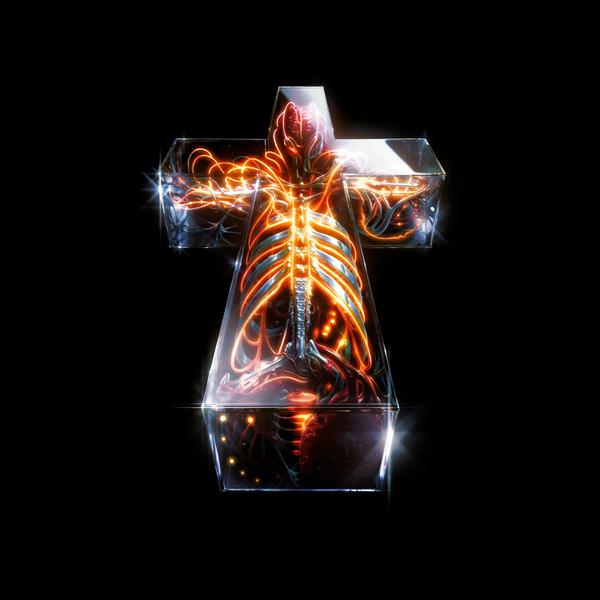

Justice

Hyperdrama

Wolfgang Tillmans

Build From Here