David Byrne – Tower Theater & BC Camplight – Johnny Brenda’s, Philadelphia 08/11/08

Philadelphia is cresting a tidal wave of euphoria. Barack Obama and pitcher Cole Hamels, hero of the Phillies’ recent World Series win, beam out from the Inquirer’s front page. No less momentously (for me at least), David Byrne is in town, playing at a gorgeous, ornate 3,000-seat ampitheatre called the Tower, where tickets top $200. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I’m the youngest person here by 15 years.

Byrne and co. are dressed in pristine white – his billowy trousers appear to be made of parachute silk – and spaced out across the stage, like the setup in Stop Making Sense. There are two drummers, on platforms of different heights, a keyboard, a second guitar and a three-person backing chorus; unlike in the film, Byrne is equipped with a guitar. The sound is slick and glossy and big: it bounces off the back walls of the theatre and buffets us in waves.

The tour is called “Songs of David Byrne and Brian Eno”, though Eno isn’t actually taking part. Accordingly, the set list draws liberally from two of the three Talking Heads albums in which Eno had a hand – Fear of Music and Remain in Light – as well as this year’s reunion, Everything That Happens Will Happen Today. We’re treated to just one song from the seminal Byrne-Eno collaboration My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, but also a relatively obscure number from The Catherine Wheel, Byrne’s 1981 score for a Twyla Tharp dance project. (Eno’s numerous credits on that album include guitar, bass, piano and “prophet screams”.)

“The River” brings an early shiver to my spine. Ever the visionary, when Byrne wrote, “A change is gonna come, like Sam Cooke sang in ’63” so many months ago, Obama’s election-night echo that “It’s been a long time coming” would hardly have been imaginable. A highly strung version of “Crosseyed and Painless” sees 3,000 soccer moms and dads take to their feet, punching the air to each yelped beat of the chorus. A slender dancer in a white tennis dress and trainers is twirling furiously, like a child imitating a ballerina. Byrne turns to face the back of the stage and twitches his arse, quickly, twice. The female half of the auditorium gasps and then wolf-whistles. By the opening bars of “Once in a Lifetime”, there is a strong smell of marijuana coming from stage right. There are now three dancers on the stage, all of them in gymnastic, arm-flailing, musical-theatre overdrive. I long for the nervy sobriety of the version in Stop Making Sense but find myself tearing up nevertheless.

“Life During Wartime” thunders into being and then into its near-apocalyptic close. It’s missing the wild, nasally keyboard solo of the studio version, but still extraordinary, as everyone on stage launches into the synchronised-jogging dance routine of the film. Byrne plows straight into “I Feel My Stuff”, a track I’ve never loved, but here the roar of its closing chorus – “I feel my stuff, I changed my luck, I’ve come back to be stronger” – is fitting and poignant. The bittersweet passage of time is hardly a new theme for Byrne and tonight he is seemingly tireless, but his silver hair and mantle of elder statesman, rather than youthful radical, is inescapable. The lights dim; the show proper is over. Hundreds of middle-aged Americans reach into their pockets and raise lighters aloft, screaming hysterically.

Five minutes later, the lights flare and Byrne launches into “Take Me to the River”. That gorgeous, watery ‘80s synth swells in and out. The aisles are packed with unruly concert-goers shaking their hips like it’s the closing scene of a Blues Brothers film; elderly attendants attempt to push them towards their seats without success. Byrne starts to hop in place like a hyperactive child for “The Great Curve”. Somehow, he looks ultra-cool, pogoing up and down and side to side like someone one-tenth his age. Then the stage darkens again.

It is a longer wait this time, but the screams do not fade. At last Byrne reappears. He is holding a metallic red acoustic guitar, smiling and apologising that the next song “doesn’t really fit in anywhere”. It is “Burning Down the House”, the only song of the night that is not an Eno collaboration. I am not sure anyone here understands, or cares. Three thousand people who are old enough to know better are pushing towards the stage, arms aloft, and shouting out the chorus repeatedly, right through the verses. When Byrne exits again, I don’t stick around to see if there is a third encore. (There is, I find out later: the stately “Everything That Happens”. I prefer my anarchic finale.) I have a date with a different man in a big-shouldered jacket.

Whilst my fellow concert-goers at the Tower file out to the carpark and warm up their station-wagon engines for the long drive home, I race across town to comparatively tiny Johnny Brenda’s, a sweet bar founded by a local boxer in the 1960s, for the second half of BC Camplight’s set. BC is a softly spoken piano man whose high, elusive vocals feed into glorious, layered harmonies. He’s most frequently compared to Brian Wilson for his ultra-complex yet catchy tunes, but equally channels 1940s barbershop quartets, the more sensitive moments of Freddie Mercury and the boogie-woogie abandon of early Jerry Lee Lewis.

Tonight, BC is accompanied by a second keyboard, glockenspiel, drums and bass. His voice is lower and growlier than on record, and he pounds out a rollicking rhythm on the keyboard, rocking back and forth on his heels and batting away the drinks that innumerable persistent blondes try to hand him mid-song. David Hartley, who doubles up in TLOBF favourites the War on Drugs, concentrates on a ridiculously intricate bassline, his jaw slack in concentration. They close with a bouncy, note-perfect cover of “Somebody to Love”. Truly, only the bravest of vocalists attempts a Queen cover, and only the most gifted succeeds. For the second time that night, I witness an entire venue erupt in hysteric, screaming delight. Here, though, I’m 15 feet from BC, rather than 15 rows from Byrne, and the smell of whiskey and sweat is a welcome change from fabric softener and Beautiful by Estée Lauder. From this vantage point, Byrne’s performance feels like a louder, glossier, uniformly energetic, note-perfect set of greatest hits, which is rather like ending Christmas by complaining that you’ve only got everything you’d asked for. Still, it’s only in front of BC’s tattered speaker stack, with an elbow in my back, one in my stomach and the cold drip of someone else’s lager on my foot, that I start to think that everything that can possibly happen has happened today.

Tower Theater photographed by Matt Pesotski

BC Camplight photographed by Lavinia Jones Wright

- Central Cee links up with Sexyy Red on "Guilt Trippin"

- Tom Smith of Editors unveils debut solo track, "Lights Of New York City"

- JADE navigates jealousy on new single, "Plastic Box"

- Amaarae announces forthcoming album, BLACK STAR

- Jade Bird shares new single, "Nobody"

- SOFT PLAY announce tenth anniversary edition of debut album, Are You Satisfied?

- Celeste details forthcoming second album, Woman Of Faces

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Loyle Carner

hopefully !

Yaya Bey

do it afraid

Haim

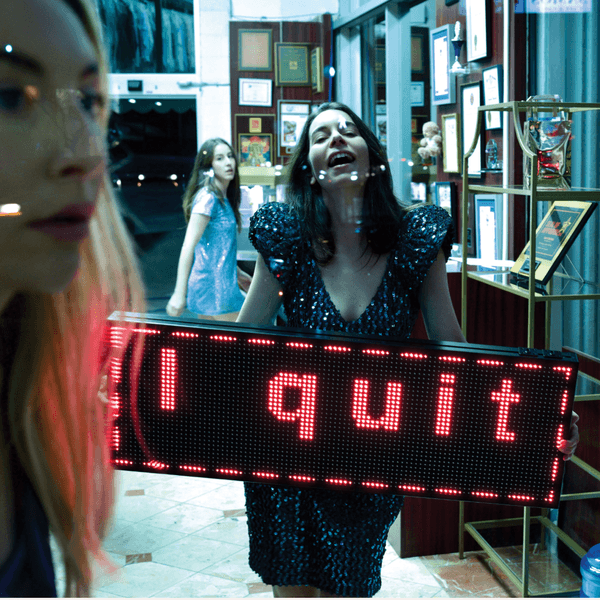

I quit