Light in dark

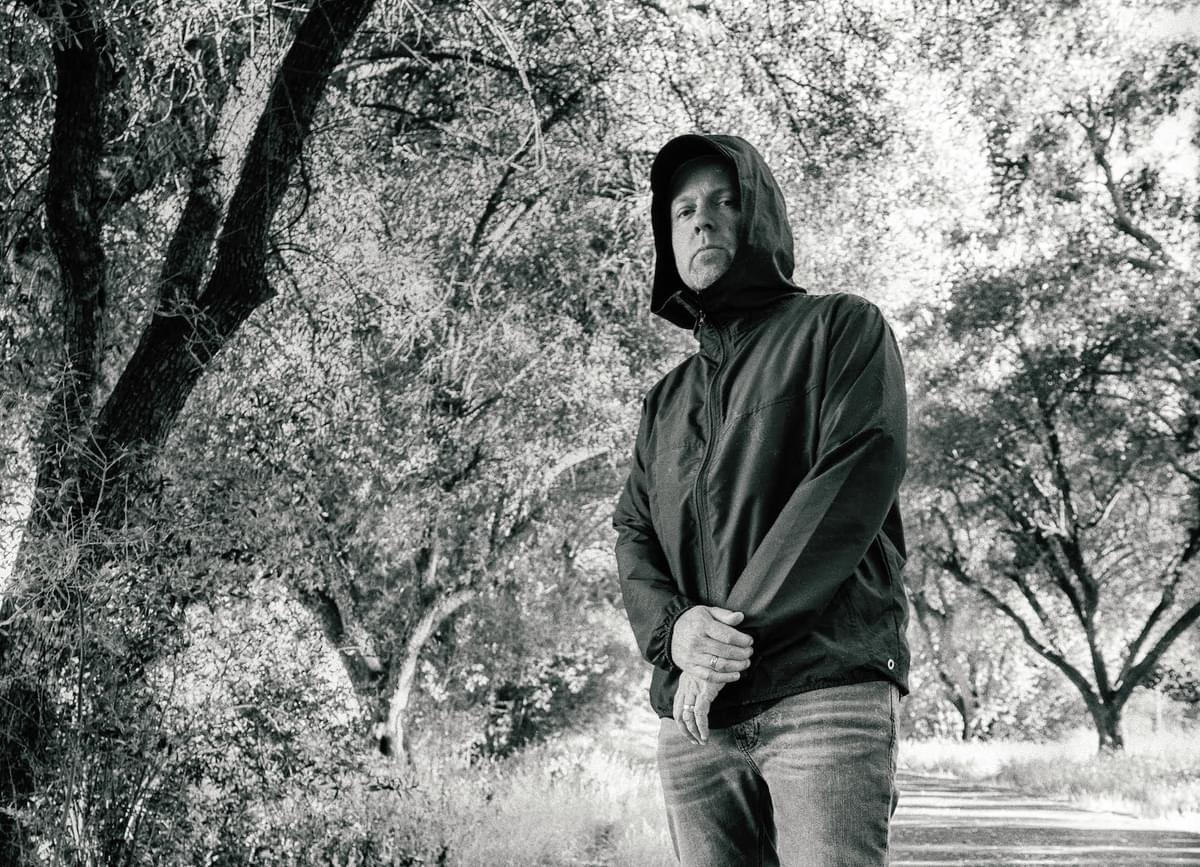

After two years spent letting life in, pioneering beat-maker DJ Shadow – aka Josh Davis – is back with a double album. He speaks to Kitty Richardson about domesticity, dubstep and embracing the void.

The opening track of DJ Shadow's new double album Our Pathetic Age is titled “Nature Always Wins”.

It amounts to just over a minute of snake-hiss static, topped by a single synth line, the two bare elements fractured under heaps of delay and distortion. The track's bleakness sets up a record that, at least in its first instrumental half, offers the listener no pacifier: the world is broken, it posits, and if it's a soothing shoulder you're looking for, you're best looking elsewhere.

Sitting down with Shadow, aka Josh Davis, in his West London hotel, I find that he's – perhaps unsuprisingly – a little adverse to the notion of escapism.

“There's something about it that's sort of ... innately offensive to me?” he says. “But by the same token, the older I get, it's almost like... a drug that doesn't do any harm. There's a part of it I detest and there's a part of it where I'm just like 'Fuck it, I can't take any more of this, I'm just gonna watch some old sitcom because I just need 30 minutes of something mind-numbing.” Davis admits he was guilty of such a slip last night, after lying awake with jet lag from his flight over from California. “The Saint was on. And it was either watch the news and all about the Thomas Cook layoffs, or I could watch Roger Moore in 1960-whatever and be like, 'This is cool, this is a bit of nostalgia'. I'm a sucker for that.”

Davis agrees that this is not what good art does though – or at least, not what he wants to do with his own. “I think that my job as an artist is to hold up a funhouse mirror to the human experience,” he states. “And these are ...bleak times, I feel like, in a lot of respects. And I like it, when, occasionally, an artist engages with that energy and tries to make sense of it.” Davis is clear that he doesn't wish to be “an overtly political artist”. But he also couldn't be content with making a party record – or even something designed to distract the listener – when the world effectively burns. “One example I find myself thinking of is Prince, “Sign O' The Times”. I don't consider Prince to be necessarily a political artist, but there's something political in choosing the moment to dabble in that energy. So while I'm not gonna stand on a soapbox and Tweet about this or that issue, I feel like I'm doing my work as an artist and voicing … the sludge and the black sky. I'm using my medium to try and make sense out of what's going on.”

That black sky is both baked into Our Pathetic Age's instrumentation and the lyrics of its guest vocalists. The first half spans everything from stuttering, avant garde breaks (“Rosie”) to anguished piano pieces (“We Are Always Alone”), whilst the second brings in a features list that 90% Hip-Hop Hall of Fame's inductees, including De La Soul and members of Wu Tang. The decision to split the record in two like this is an intriguing one, and Davis admits, with mild disdain, that there’s a reason previous efforts have sandwiched rap so squarely between other genres.

“I became really irritated at a point because people who became enamoured with my music seems to not like rap music at all,” he says. “And whenever I did rap music, they’d be like 'URGH'” – a snort of disgust – “‘No! Go back and do your other stuff! And I'd be like, ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’ Because I'd always done rap stuff.”

“So I have done several albums in a row where I forced the issue, almost like throwing a gauntlet down to my fanbase. My format was – you're gonna get David Banner next to an ethereal female vocal song. If you're really a fan, you're gonna get it all, I'm not gonna spare you anything.” I wonder why this changed; whether, as rap has become such an omnipotent force in today’s charts, Davis felt that people would simply be more comfortable hearing emcees atop his production. But he explains it was purely to create space.

“I wanted to have the opportunity to let the instrumental music breath on its own,” he says. “And I didn't wanna figure out all the connecting points – almost like a DJ set, like ... how the fuck am I gonna transition back into this, and how am I gonna get out of this and back? And it dawned on me, I was ready to do this. The double album thing was a suggestion made by someone early on. And I stuck it in my back pocket and didn't really tell anybody about it – I just decided I was going to try.”

Just nipping back to the rappers for a minute, the LP hosts a real roll-call: the aforementioned De La Soul, Ghostface and Raekwon join Nas, Pharoahe Monch, Run the Jewels, Wiki and Pusha T. There's even a bonus track appearance from the South West's own Barny Fletcher, which makes the age gap between emcees about 30 years. I ask Davis if he sees a difference between the old guard and the new blood.

“Honestly, everybody is so different,” he says. “Some of the older guys that I've worked with fit what you might imagine in the sense that, maybe they are quite set in their ways. And then there are others who really have the desire to be creative and, they still love it, as I hope I love it. There are shades of conservatism in both groups – so, with the older guys it's like, 'How is this gonna benefit me? I've done X, Y and Z, and wanna make sure this isn't the red mark on my record'. If you're calling after someone who's young and hot, they're immediately suspicious. 'Everybody wants me, why should I be on your shit?' That's the sort of mentality, it's a hustler mentality. 'I only wanna make hot shit that's gonna be on this rap playlist, that RapCaviar's gonna put it in there...'. It's interesting – let's put it that way – to see who climbs on board. Because what I'm offering people is not a slam dunk.”

I note that part of the arrogance displayed by very young rappers might be a symptom of how quick the come up can be now, with the internet having somewhat flattened an industry that used to take years and years to penetrate. He nods. “For ages I was able to say to people that all my favourite artists tasted failure before they had success. I mean, one after another, after another – everyone failed before they made it. Now, you can be like, 'I'm gonna make a YouTube video' and it blows up and the next thing you know you're in an Apple ad. It's great that [the industry has] been democractised in that way, but it also means that some artists get so big so quick, they get a little twisted, and then don't have that benefit of experience.”

Davis, of course, does have the benefit of experience. His 1996 debut album Entroducing had a seismic impact on the would-be beatmakers at the cusp of the millennium: you can hear the influence of that hyper-creative sampling and his sumptuous arrangements in the work of everyone from Blockhead and RDJ2 to The Gaslamp Killer and even Fly Lo. But having established such a distinct sound so early on in his career, he spent a good few LPs trying to wriggle out of it. 2006's The Outsider famously landed with “3 Freaks”, a club banger that sounded more B-Pitch than boom bap, and marked the first time Shadow fully joined forces with rappers. Later, he would drop the brooding, guitar-heavy The Less You Know, The Better, featuring collaborations with Little Dragon and Tom Vek. And on The Mountain Will Fall, electronics took the foreground, Shadow's sad-cinema sensibility surviving through a sound that, despite its humanity, was comparatively inorganic. Davis volunteers that the last big shift in his artistic process was in part down to him falling for everyone's favourite love-to-hate genre, dubstep.

“Once I first heard dubstep I was like, this is where the musical zeitgeist is,” he enthuses. “It's not in hip-hop or rap. Because I'd been massively inspired by Southern rap since the mid 80s – groups like The Ghetto boys, Miami Bass stuff, 36 Mafia. But I'm always trying to figure out where music is doing something new. And even though I love rap, it's like 60/40 the music. If the music is dope and the rapper is so-so, I can kinda roll with it – but if the music is whack and the rapper is dope, I just can't.”

“And dubstep made sense to me in the same way that drum and bass made sense to me. Like, occasionally they'll be something that comes along that maybe only has a very tenuous link to my bedrock of hip-hop. But the link is there. That's my lifeline, I can use it. And then as dubstep because bigger and more Americanised and even more aggressive and more EDM... and then it became 'post dubstep' and the prototrap stuff around 2012... I mean, I was listening to all that stuff.” Davis explains that, as a DJ, part of his quest is to find “the biggest, baddest, nastiest monster in the room” – aka the track that is going to destroy the dance. “And honestly, once some of that really big, really aggressive dubstep came out, it just blew everyone else away. I remember seeing a Grammy Awards when Deadmau5 dropped this dubstep track. And I remember Dave Grohl was standing at the side of the stage and you could see this look on his face like, 'Oh fuck, rock and roll can't keep up with this shit'. As an observer it's hard not to be affected by that.”

Davis is pretty self-effacing when it comes to talking about his musicianship, and says that it was only when he came into contact with this all-consuming, chest-rattling wave of electronic music that he started to pull his production socks up. “As a producer and engineer I wanted to know how that stuff was being made because I did not have the foggiest notion,” he smiles. “And so I started reaching out to artists that I respected on the scene. Most of them were about 20 – and coincidently, a lot of them were from the Bay Area. Even though, like, I was listening to them on Soundcloud and they could be from Russia or New Zealand … one by one it came out that there were all within like, 50 miles of me. And I started going, 'Well, that's not a coincidence.” It was working with these fresh-faced producers that added some more technical strings to Davis' bow. “I think that's what allowed my production to expand. I started to understand how to harness sound, how to make it do what I wanted it to do. Because prior to that, I was always a bit lost on an engineering level. I didn't even know what side-chaining was! I remember when I didn't know what compression was... or filtering. So many basic production techniques.”

Our Pathetic Age marks a return for Davis after a healthy pause – in fact, today's interview is on his first promo day in two years. Aside from being kind and engaging, he strikes a reasonably introspective figure, and confides that talking about himself isn't his preferred mode. “I mean, I think I'm about as reclusive as you can be in 2019. I'm not on social media really … and if you're not on social media, are you even alive?” He gives a tight smile. “I feel like if I was any more reclusive than I am I'd be a bit worried.” His decision to withdraw from modern-day connectedness has major positives – mainly that he's much happier. But there are drawbacks. We discuss the alarming speed with which you seemingly cease to exist when taking a break from Facebook – and the way in which all our news is now aggregated through feeds and timelines.

“When I was on [Twitter] I probably followed three four, hundred of people who I saw as interesting peers, people I respect and wanna hear from,” he explains. “And like, just the other day, I didn't know that Ric Ocasek [of The Cars] passed away – and I'm not the biggest, most devout Cars fan but you think that I would have heard? Or this rapper or that rapper. It's like, I kinda wanna know when people are no longer walking the Earth, and I realised that if it wasn't for social media, I wouldn't.”

“But for the purposes of creating, I know that I need a positive headspace. And I also know I can't have a positive headspace if I'm actively involved in social media.”

For all the positive headspace that Davis' analogue existence allows him, coming to write the new LP was, in his own words, “daunting”. “Especially after you've done half a dozen, 8, 9, whatever it is. Because to me, there is a lineage I'm trying to live up to.” Davis' little tale about skill sharing with dubstep artists is just a tiny insight into how passionate he still is about getting it right and the weight – perhaps, pressure – which he bestows on his own originality.

“I never wanna repeat myself,” he says with insistence. “I want people to know that the work was never... sort of sloughed off, and 'I'll take a shortcut'. I want people to hear the incredible amount of effort that's gone into it. And I always want to have something new to say with a body of work.”

“I've heard authors talk about … where you start a project for real and it's an official thing and you're like 'Right, I'm doing this now'. And you psych yourself up. There can be three weeks of this incredible creative output and then you get a bit spent. And you step back and you say 'OK... but I can't stay away for too long'. And that's where it can get very difficult.”

I ask about the track “My Lonely Room” from the new LP, and whether the title spoke to his own experience locked away in his studio. “Well, I'm just one person making music – I don't have a band, I don't have a vocalist who's gonna come and do this and that. So it is a bit lonely for me. And what happens is that I start engaging with personal demons and… stuff that, from now until I tour, I don't have to deal with. But when you're doing something creative I feel like I have to confront things. So yeah, it's a tough time.”

“And that song title just kind of came out. I wrote it down because it seemed to be speaking to the song that I was working on. I like my music to reflect the entirety of human experience, from happiness to sorrow. And when you're working on the sorrowful tracks, it can be a lonely thing.”

Despite the isolation necessary to birth an album, Davis says he's lucky to have a life outside his chosen industry. He's married, now with two little boys, and seemingly basking in the stability and security of domesticity. “I definitely have allowed life to come in,” he says. “I didn't want to ever be the kind of artist who was on an assembly line. And whether it's getting married or having kids, I always knew it would make my music better.”

“And I see now, in retrospect, how so many people aren't able to sustain a career once they have a family. I totally get it. Because family life is seductive. There's no place I'd rather be than with my kids. But, but the same token, I think it's healthy for them to see that ...pursing an artistic way of expressing yourself is a privilege and a rare opportunity. And if I ever get to a weird, ugly place, I can go 'I still wanna love what I do, so I'm gonna disengage and pull back for a minute. And, good news kids, we're gonna spend a bunch of time together! I'm gonna be home for two years!' I was able to be present for a big chunk of time in their life and not have them worry like, 'When are you leaving again?'”

“Plus, it makes [returning to] the music feel like a joyful process rather than 'Here we go again'. That's why I'm always a bit wary of turning back to the well that quickly.You've got to give it some time to refill.”

To Davis, refilling also means pursuing other projects that don't fall into the cycle of record-release-repeat. Recently, he was asked – alongside friend and collaborator Cut Chemist – to take Afrika Bamabata's private record collection on tour, a project that he still doesn't seem convinced he deserved to land. “It was this incredible honour and opportunity,” he says, a tad dreamy-eyed. “A six month diversion that was well worth our time. We put a set together with like... some of the records had cracks this big” – he makes an L shape between finger and thumb – “going down to the grooves. And seeing the tags of Black Spades on the labels... you can't get any closer to hip-hop history. If I had been super-regimented and said to myself, 'Oh you need another album', I probably wouldn't have been able to do that.”

As we wrap up, I'm conscious that our chat might have dragged Davis – someone who seems to pride himself on connecting with the world's darkness – into a bit of a hole. Clumsily, I ask about hope – can we find some chinks of light breaking through Our Pathetic Age, despite the potent framing of its title?

“I think there are hopeful moments on the record – because I think that's important,” he says. “To me, the human experience is all about light versus dark, yin and yang, and that to me speaks as to who we were, going back centuries and eons.” Having penned records that scored the lives of so many, Davies feels overwhelmingly fortunate that his music has brought peace to those trapped in the same noisy, chaotic universe.

“The analogy I'll use – and it's probably not very original – but there's no telling where the ripples are going to go. Once the music is out into the atmosphere, the last thing I would ever want to do is dictate who can listen to it, what they're going think, how it's going to be received. It's here, it's yours now and I hope you like it. And maybe someone who's experiencing some trauma or trying to get through something will find something in it.” For Davis, the tales fans tell him about how his music has helped them – the listener who used his LPs to banish suicidal thoughts, the friend who’s roommate chose them as a coping mechanism for surviving cancer – remains uncanny. “Especially at the beginning of my career, I was told a lot of things like that. I mean, you hear these stories and you go, wow.”

So, whilst not wanting to give his listeners something ignorant of today’s fraught sociopolitical context, Davis does want to create something cathartic – to quell the anxiety he feels radiating from others “just walking down the street”. And if the album is bleak, its impact surely won't be. “That's why I wanted to make music in the first place – because I wanted to contribute. I wanted to offer an individual voice that someone, maybe, somewhere, would latch onto and it would help them process. In the way that all the records that I love have helped me process.” He pauses, then gives me another apologetic smile. “It's a long answer, sorry.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex