D'Angelo's magnum opus, Voodoo, stands tall as the towering achievement of modern soul and R&B

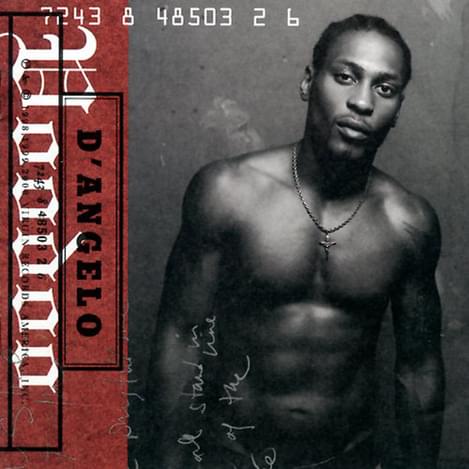

"Voodoo [Reissue]"

D’Angelo made those comments some time in 2000, when he was promoting what we now know to be his magnum opus, Voodoo (recently given a long-overdue vinyl reissue). The lay-off of five years between that record and its predecessor, 1995’s Brown Sugar, looks positively paltry in retrospect, set against the fourteen years the world was made to wait for the album that was originally known as James River and would eventually become the fiery Black Messiah. If ever the term ‘rush-release’ has been used with scything irony, it was in relation to D’Angelo’s decision to drop that third LP in the no-man’s-land of mid-December - in response to ongoing racial unrest in America - rather than stick with the already-slated date of early 2015.

There’s certainly no shortage of entirely feasible explanations for those wilderness years that followed Voodoo; disillusionment with the music industry, drug and alcohol issues and D’Angelo’s well-documented track record of perfectionism to a fault are all amongst them. The question of whether the passage of more time than his two-year tour for Brown Sugar constituted was necessary for the thematic material that makes up Voodoo itself, though, is another matter entirely, and one worth saving for a little later; after all, this album’s strength lies primarily - but by no means exclusively - in the sheer virtuosity of the musicianship on show.

D’Angelo is a man of prodigious talent, and on Brown Sugar, he demonstrated as such; he recorded the vast majority of the instrumentation himself, sprinkled in clever guitar licks and smartly considered orchestral flourishes with a wisdom beyond his years, and applied real intelligence in keeping the entire piece so unremittingly economical. Accordingly, the album is a study in restraint and minimalism, but there was perhaps always the sneaking feeling that he might have been underselling himself. Sure, that approach was far preferable to him throwing everything he could at the record for the sake of it - bringing in every possible big-hitting guest, attaching bells and whistles to every aspect of his instrumental repertoire, and putting his inimitable falsetto very much front and centre - but at the same time, Brown Sugar felt in some respects as if it only represented the tip of the man’s talent.

And so, on Voodoo, it would prove. This is a record that has few, if any, points of genuinely valid comparison. Brown Sugar was easy enough to pick apart; R&B with flecks of soul, jazz and hip hop. Voodoo is a different beast entirely. It by no means does away with those points of genre reference; instead, it expands upon them tenfold. Across thirteen tracks, the complexity of the stylistic construction takes the breath away. This is no longer an R&B record with nods to other genres; D’Angelo brings in his soul influences wholesale, pitching the album halfway between them and something else entirely, something that, in many ways, provides the genuine lifeblood of the record - funk.

On “The Line” or “Chicken Grease”, you’ve got a veritable chorus of D’Angelos singing at you - these multi-layered, harmonic vocals, a new development post-Brown Sugar, seem to have held the key all along to him having uncovered his true soul man. In anybody else’s hands, you suspect that this kind of delivery wouldn’t work when set against an instrumental backdrop concerned mainly with groove and texture, but it comes off spectacularly. The ultimate result is that whilst D’Angelo sounded aggressively focused on Brown Sugar, he absolutely strolls through Voodoo. More than that, he positively swaggers; this was one of the last huge records of the pre-digital era, of a time when artists on majors could take as long as they needed to find their stride - the confidence that oozes out of every proverbial pore here suggests D’Angelo did just that.

After making Brown Sugar with limited outside involvement - especially surprising in terms of the lack of collaborations, which were staples of the R&B genre at the time - he was more open to the idea on Voodoo, especially given that both Common’s Like Water for Chocolate and Erykah Badu’s Mama Gun were being recorded at Electric Lady in New York at the same time. A loosely collaborative atmosphere ensued at the studio, with Questlove - on production duty on both Common and Badu’s albums - quickly taking his rightful place behind the kit on most of Voodoo. Those three records would quickly come to form the crux of the finest output from the Soulquarians, the soul and hip hop movement that counted those artists as members alongside the likes of Mos Def, Q-Tip and the late J Dilla.

When D’Angelo gave a lecture at the Red Bull Music Academy last year, he said, “I never claimed I do neo-soul. I always said I do black music.” His more relaxed attitude to the idea of working with his peers held the key to the complex, intelligent and ultimately, more visible way in which he referenced his black influences on Voodoo (funnily enough, the biggest obstacle faced early on in sessions for album number three was that he wanted to go back to doing everything himself, an indicator of his ongoing fixation with Prince.) “Left & Right”, with a well-judged guest turn from Method Man and Redman, didn’t just nod to hip hop - it incorporated it. "Devil’s Pie" chops up no fewer than six samples from the likes of Fat Joe, Raekwon and Teddy Pendergrass; having master sampler DJ Premier behind the desk on that track couldn’t have hurt, either. The verses on “One Mo’gin”, meanwhile, are straight-up delta blues, and whilst he’d tackled a quiet storm-style blues cover before with “Cruisin’”, his take on Roberta Flack’s “Feel Like Makin’ Love” has been moulded unmistakably into his own style - in fact, it was originally intended as another collaborative effort, with Lauryn Hill, in the early stages of production.

Questlove told Spin that the fluid nature of the album’s personnel made Voodoo’s recording sessions feel like “a left-of-center black music renaissance”; you kind of get the impression that it wasn’t until years later that those involved realised the degree to which they’d captured lightning in a bottle. This was a special kind of alchemy in instrumental terms. Questlove, on drums, worked with Dilla to put together programmed rhythm tracks that, by design, couldn’t be distinguished from a live kit; in one of the record’s many ingenious instrumental turns, they would deliberately fuck with the inch-perfect programmed tracks to lend them a human feel, resulting in the languid - almost sloppy - percussion that stands up as one of Voodoo’s hallmarks. Another of those is Pino Palladino’s contribution; his basslines are of monstrous importance to the album’s sound, particularly on “Devil’s Pie” and during the so-called “virtuoso part of the record” - Questlove again - that comprises “The Root”, “Spanish Joint” and “Greatdayindamornin”. All three were recorded totally live and are riddled with the kind of elaborate twists and turns that you can get totally lost in - however many times you hear them, you always come out the other side feeling like you’ve picked up on something new. Of particular note on that hat-trick are Charlie Hunter’s smartly considered guitar lines, as well as D’Angelo’s gravitation towards Latin jazz on “Spanish Joint”.

In 2015, with the benefit of hindsight on Voodoo and Black Messiah, there’s no question that D’Angelo is a genuine intellectual; his take on America’s recent civil unrest along racial lines on the latter record, for example, was clearly born of both deep thought and real soul. Listen to Brown Sugar, though, and the themes feel relatively rudimentary; a bunch of love songs in a classic style. Voodoo saw a wholesale expansion in conceptual terms; lyrically, he ruminates upon faith with real depth, as well as studying maturity (“Send It On”), psychological challenges (“The Line”) and, quite prominently, his then-recent entry into fatherhood - closer “Africa” deals both with that and his heritage in general. On top of that, he cherry-picks ideas from his favourite genres to suit both his own tastes and the album’s cerebral approach; “Playa Playa”, for instance, embraces the traditional competitiveness of hip hop, but “Devil’s Pie” is an out-and-out dismissal of its obsession with material wealth. The fact that the lyrics are actually difficult to discern on first listen for the most part, thanks to the heavy, Let’s Get It On style vocal multi-tracking, is one of many excuses to less give Voodoo repeat listens than approach it with the same meticulous ear for detail that D’Angelo himself lent to it in the studio.

And then, of course, there’s the penultimate track, and his most famous. “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” is ultimately better-known in the popular imagination for extracurricular reasons; the video, which features nothing but an apparently nude and by no means gym-shy D’Angelo against a black background, turned him into an unlikely - and reluctant - sex symbol. Both the track and the video utilise a sledgehammer touch that contrasts jarringly with the album’s otherwise largely subtle approach to sexuality, and the ensuing attention at live shows - with feverish female fans packing shows more in the hope that he’d flaunt his torso than deliver a musical tour-de-force - was a major factor in forcing D’Angelo into the reclusion - and substance abuse - that kept LP number three on the back burner for so long. That shouldn’t, though, detract from the quality of the song itself; if you’re going to shoot for unabashed sensuality, at least do it like this. Prince, again, apparently provided the inspirational blueprint for “Untitled”, but Gaye, White, Wonder and Summer are all in spiritual attendance, too, in a manner that made the likes of Boyz II Men and Ginuwine sound trite by way of comparison. “Untitled” was released as a single on January 1st, 2000. The next millennia of R&B songwriters have plenty of time to top it, but I still wouldn’t hold my breath; it’s hard to imagine anybody absolutely nailing sensuality like D’Angelo did with this cut. It’s brazen, but still nuanced.

Like the reissue of Brown Sugar, this new press of Voodoo isn’t a remaster, and again, why would it be? It often feels as if D’Angelo was walking a bit of a tightrope by making the album so unrelentingly complex - there are so many deft touches, and so much going on at all times, that to go back and tamper with either the mix or the masters would surely detract from what makes Voodoo truly great. It’s an album scored through with tiny intricacies; the little instrumental turns of phrase and carefully woven textures make this a masterful construction project, but the scarcely-there spoken word snippets that wax and wane in and out of the intros and outros mean that it’s a human one - you can feel Electric Lady circa 1999 living and breathing on this LP. It is at once both intimate and monolithic. In terms of twenty-first century soul, R&B and funk - even blues - it is utterly without compare.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Patrick Wolf

Crying The Neck