Label Love: Constellation Celebrates its 15th Anniversary

While in Montreal earlier this year, we headed up through the torrential rain to the Mile End of town, past old warehouses now converted into offices, to the building that acts as headquarters, warehouse and home to one of Montreal’s most well known labels, Constellation. This year marks the labels 15th anniversary, which they will celebrate this month with a series of shows across Europe with some of the label’s longest running active artists including A Silver Mt. Zion, Do Make Say Think and Sandro Perri amongst others. We catch up with label co-founder Ian Ilavsky to find out about how things have changed since the label put out their first release, Sofa’s New Era Building on 30 May 1997.

I begin by asking how important Montreal itself was in the forming of the label. The city is one of the most politically active in Canada, and the question of separatism for Quebec is a controversial one that occasionally crosses the line into violence. . Combine that with the different cultural lives of the Anglo and Francophone Quebec and the geographical location and the city stands as somewhere quite unique. Ilavsky, who originally hails from Winnipeg, in not comfortable being definitive about its influence but points to a few things that certainly had an impact when forming the label. “The most obvious thing about Montreal in ‘95 was how incredibly inexpensive the city was. The overall state of economic stagnation in the city made everything cheaper. Montreal was the de facto economic capital of Canada until the Quiet Revolution of the late 60s. After that, the rising Quebec nationalism pushed a lot of anglo wealth out of the city, and particularly banks out of the province, they left a lot of spaces to use. That helped us to stay extremely lean in our overheads compared to Vancouver or Toronto. The city also attracted internal Canadian artistic exiles, but to come here you had to have cultural courage – you weren’t going to get a warm welcome.”

Meaning what exactly – were there threats of physical violence? It’s an idea that makes him chuckle, so much so that he brings up the idea in a panel debate the next day. In reality, he says, you could expect hostility but “no one lived in fear of being beaten up by marauding francophone youths.”

The cultural context also was “less straightforward than those in Chicago or Toronto or New York at the time, where there was a clear distinction between overground and underground cultures,” he suggests. “When we started we had an inward looking self sufficiency. We didn’t expect to find validation or crossover. Those ideas sound quaint now: the notion of exposure of crossover now with the Internet is so different.”

Constellation’s first location was in Montreal’s Old City in a building co-owned by Patti Schmidt, who was the host of the seminal Brave New Waves radio show at the time. “Brave New Waves was pretty much the only state radio nationally that would play real out-there stuff. It earned its title. It didn’t play pop music unless it was extremely art-damaged and had whole sections for overtly out there stuff… you would have cut up college artists sat next to snarling punk rock or academic music or modern classical.” The building dated from the 18th Century, and housed a commercial space on the mezzanine level as well as a number of artists spaces. “Don and I rented a 1500sq ft room and lived there and did the production and assembly there too. We ran a kind of special music series there as well called Musique Fragile. It wasn’t meant to be a testing ground for Constellation artists but it was a response to local conditions that were extremely difficult for anything experimental or requiring a little more listening attention.

“At the time venues were run by club owners who only cared that you were out by 10.30. For the privilege of soundchecking and playing a show between 6 and 10.30 you had to pay them 350 dollars. No one could afford to spend 5-6 bucks a show so it was charity. Someone might take a risk and hire a bigger venue like Cafe Campus, which was the least offensive of them all, as they knew there was a crowd for live music. You could put on 5 or 6 bands and get 250-300 people which would be a huge crowd.” Although the venue situation is much improved now, more out there shows still regularly get busted. But, as Ilavsky muses, that tends to be the nature of the beast: “They have a short life-span. Not because they get co-opted or shut down but for the fact that it is exhausting running something like that, especially if you live there too.”

What came out of these events, eventually, was a record label to support the community that they were part of. “We couldn’t identify a home grown label we would send a demo to. What we did at the time was put out our own cassettes. Now people are doing that again, although now its freighted with retro-mania. You can just as cheaply burn a CD-R now but that wasn’t the case then. But our concerns were far broader than starting a label – our horizon was local and represented what we saw as a largely anglophone group in exile of the larger cultural context. We did no research. We thought we were going to sell out the back of a van and at shows and then tour locally as anywhere else was so hard to get to. From the day we started to get attention our interest was in talking about cultural production.”

“We felt part of a history in line with the likes of Touch and Go and Dischord. We do things for a reason. We could be baking bread, or books. It was important to us to be enacting a way of producing culture and putting it in to a market place in a way that felt engaged and principled. And we didn’t have to tell the story – people read the record sleeves, or read it into the music.” The success of Godspeed via word of mouth with no publicity brought the interest of distributors and allowed the label the fortunate position of being able to choose what fitted them best. In Southern they found a group of people who understood. “They told us our options and that they would never have to explain why we did or didn’t want to do things. They just understood. It’s the same relationship we try to have with our artists.”

{pagebreak}

By 2000 the original office space no longer had room to host shows, as it was full with stock and assembly. As a result of doing the non-conventional packaging and sourcing all of the materials themselves, the production line was the office itself. Although the label has mechanised more now and do a lot more straight offset printing of packages, much of the packaging is still assembled at the new office (which remains a home to Don). “As much as anything it was fueled by a desire to provide work for musicians – it was a way for them to get a living wage for casual labour between tours. These days we have a full time warehouse guy who makes the calls if he needs to get someone in, so it’s less of a revolving door. It’s a fact that we are at best doing the same amount of physical as we did ten years ago. For a label with more underground artists, vinyl is more robust than it was – we might press 800-1000 instead of 300-500, but the CD side has dropped significantly.”

The shift in the way people consume music presented an obvious challenge to the label, and has forced them to adapt their operation over the years. In the early days, the label did not, by and large, access Government funding packages. “To an extent we didn’t think we would get access to them, as it was a very Francophone based system in Quebec. Certain bands certainly tapped it from time to time in the early years for tour funding and we would support them with a letter, but there was never any funding for day to day costs or recording. Perhaps we felt wrongly that we had no chance, but we also had pride at being truly independent… However, by the middle of the last decade it became apparent that other contemporaries such as Arts and Craft, Paperbag or Mint were tapping this stuff. At the same time the CD, the real margin format was taking a beating and the financial markets that had been in our favour were now on a par with the US dollar. We looked around and saw that those other labels were putting out way more commercial releases. Our choice was to apply for funding or start aggressively monitising in other ways, which really was the last thing we wanted to do. We don’t want to be a marketing company.”

This commercialisation of music is one that Ilavsky unsurprisingly feels strongly about: “In 2012 it isn’t a shocking statement on Constellation’s part to say that so called “indie rock” has been thoroughly and truly commercialized in the sense that if you are trying to make a living as a musician the most obvious thing you would do is sell your music to commercial interests first, not to fans. To give a product a hipster quotient. These synergies are the air that a whole generation of kids – raised with the Internet as their main porthole for arts and entertainment – breathe. A lot of indie labels are taking a page, and in some cases the whole book, from the major label plays of the 90s, the book that we always rallied against or would say ‘This Book Sucks’. They are ready to aggressively market or sell anything: music or personality. It’s an easy era to say ‘Fuck that for being popular’. The only thing that is important to us, is that we have always shared a horizon of what a career means. Efrim says over and over again that making music is work and you should make ethical choices about it as you would do in any other field. You have to reconcile that at some degree you might be considered an entertainer but that doesn’t give you a free pass on the nasty options that it throws up at you. Those nasty or compromising choices are now barraging artists because it is hard to make an honest living.”

“We feel like we can hold our heads up high because a lot of these releases are pretty fearless, pretty non-commercial so we felt as deserving as anyone else. We had to hire a part time accountant, Dan, and he took on a lot of that. Without him we probably would have had to downsize. The goalposts shifted and we’ve adapted to them.” This decision has allowed the label to maintain its artist friendly principles. While Ilavsky insists that Constellation has never required its music to be political, the decision behind the scenes at the label are. Thus while bands on the label will never be allowed to put their music in an advert, the label gives 100% of any movie or TV synching to the artists. “That can be a vital paycheck for them. We’ve never reneged or backpedaled on it and it has allowed us to say ‘fuck it we’re going to go for a grant’.”

The way in which artists find exposure, or over-exposure, is also something that has changed drastically over the last 15 years. When Godspeed first started getting attention overseas it was unlikely that the office would pick up the phone to journalists, particularly music journalists. “Why would we pick up the phone to some guy from Spin who was calling because Montreal was ‘hot’?” At this point Ilavsky puts on a pretty impressive Californian drawl, “You guys are all hippies living bare-foot in a squat. You’re crazy. Tell me more!” However, he acknowledges that eventually journalists did come out of the woodwork after more than a superficial story – mostly from the broadsheets, who were already conversant with the more political aspects and background of both the band and the label. Then, as now, he suggests, there was a degree of chance and tapping in to something special in order to prevail: “Godspeed tapped into a zeitgeist and became standard bearers for post rock. Because of the way they did it, at the very least journalists had to take some initiative. But equally we had to combat the notion that this was all a very sophisticated marketing campaign. It wasn’t. These days to be mysterious actually requires concerted effort.”

For a label that set out with a very local focus fifteen years ago the landscape has changed dramatically. And not for the better. The constant barrage of the new and the clamor for the latest breaking thing has created a new international jet set community with a set of ethics uncritical of certain choices that just a few years before would have been rallied against by what was then termed ‘indie-rock’. “It’s more affordable. You can internationalise on Internet buzz and make good money live without having played a show. But the choices that you have to make… It’s hard to argue that we aren’t in a golden age of do-it-yourselfism – the ways and means you can do things are broader. But the idea of validation on a global scale is terrifying and there are no meaningful boundaries anymore. And there should be given how fucking bankrupt the overall system is.”

“It’s like we are all just partying like its 1999 and getting it while we can, and I feel there is a huge level of nihilism in that sense, especially with cultural practitioners of Indie-rock. Now everyone has a larger sense of agency. Pitchfork might get a million page views a day but 990,000 are people in the industry doing ego scans, consuming each others work. No one wants to take away from a kid wanting to get out there and make something but the usual machinations of industry are just plucking them out. And even in the alternative world what gets plucked is that which is strongly conversant with pop. Because the only way to sell a record these days is to the fly by listeners that only buy 5 or 6 a year. Out of a pack of bands doing the same thing one might gain a foothold and be the one art-rock record that 40,000 people buy in a year. Or you can stream it all without spending a dime.”

On the subject of streaming it all, almost the entire Constellation back catalog, with the exception of Godspeed You Black Emperor! (i.e. prior to Yanqui UXO when they became Godspeed You! Black Emperor) are available to stream in full through Soundcloud, and have been available for two years. I ask Graham Latham, the in-house publicity officer about the thought processes behind this. “I think it’s important to describe it as a good faith gesture. We would hope that fans understand that at some point it cost to make it happen.” Ilavsky adds that they figured that it couldn’t do any harm and might help as a discovery tool for other bands on the label. “We have been talking about doing a take down for the last few months however. I’m not sure that it is being perceived in the ethical and political framework in which they were provided. That isn’t to say we don’t love Soundcloud, rather we are going to be more robust in the way that we use it. We will probably use it to stream new albums for a limited time and to premiere new material. It’s part of our increasing, albeit slow, reckoning with social networks.”

While the world in which they operate may have changed over the last 15 years, it is clear that the fires that drove Constellation still burn bright. The label continues to strive to uphold the principles that it was founded upon, and produce releases very much on their own terms. As a result they have continued to put out challenging, thought provoking and beautiful records. We can only hope it continues long in to the future. Happy Birthday, Constellation.

To mark the 15th anniversary shows across Europe, Constellation have put together this playlist featuring all of the acts performing at the shows in London, Munich, Vienna and Leipzig and beyond this month.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Loyle Carner

hopefully !

Yaya Bey

do it afraid

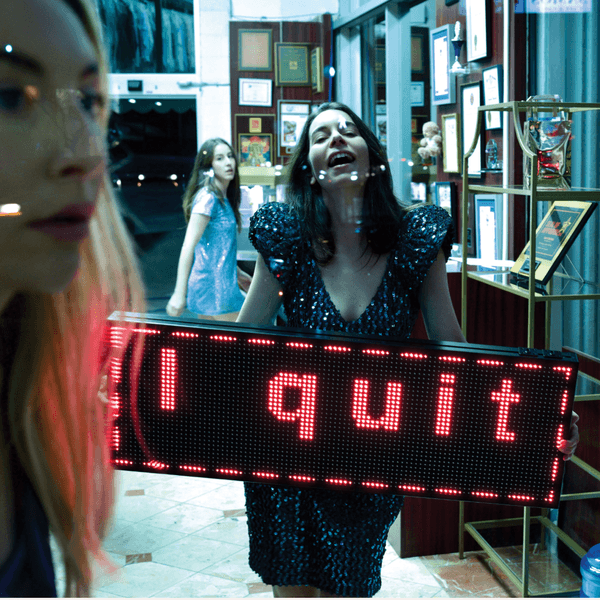

Haim

I quit