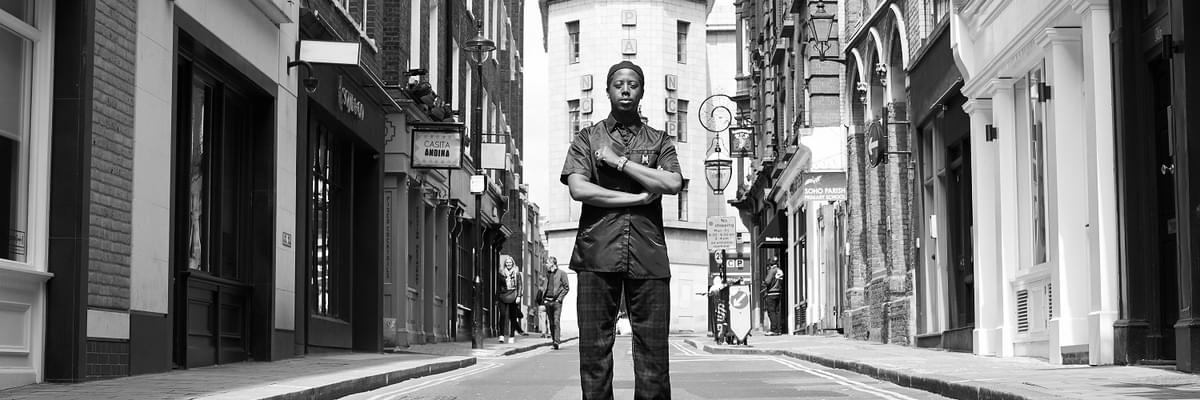

London jazz sensation Moses Boyd takes Dinesh Mattu on the history of the origins of Jamaican Jazz and the importance his heritage plays in the UK’s musical identity.

“Some stayed, some went to England, some went to America, but the influence was equally as strong wherever they were. There’s something special about the island. Maybe it’s something in the water - or in the rum, who knows?”

Revered worldwide for its contributions to sport, culture and the arts, it seems that the tiny island nestled in the Caribbean Sea with a population less than that of Berlin shouldn’t - on the face of it at least - have the right to bear such global weighting. The legacy of its most prominent son, Bob Marley, can be seen from the market stalls of South East Asia to the shop windows in the cobbled streets of Europe. There is no doubt that Jamaica’s unassuming size contradicts its global authority.

Synonymous with Reggae, Bashment and Dancehall, the island has influenced everything from style, to language, to religion, particularly in the UK where many of its Windrush generation came to settle in the ‘40s and ‘50s. Unbeknownst to some though, is the long lineage of jazz originating from Jamaica; a direct source of inspiration for many of the UK’s notable torchbearers today.

For a genre which traces its modern-day roots to 1920s New Orleans, the jazz movement took on a new lease of life when it hit the palm-laden shores of the Caribbean. Over the proceeding decades, pioneers such as Joe Harriott, Rico Rodriguez, Eddie Tan Tan Thornton and Vin Gordon all contributed heavily to Jamaica’s rich tapestry, and as jazz grew in popularity and bands toured across the world, many of these names and their respective sounds eventually found their way to the UK.

As a descent of Jamaican heritage and one of the central characters in the wave of the so-called London ‘nu jazz’ scene, Moses Boyd explains how his motherland and those pioneers have influenced his output, “I think within UK jazz we stand on those shoulders,” he says, “The UK is very indebted to Jamaica's contribution to music, culture, to style, to everything. It’s good to be able to see where I sit in the continuum of being a descendant of all of this and being able to wear it with pride - like, these are my people, and this is what we've done.”

Recognising the influential contribution that Jamaican music and culture has had on jazz in the UK, the drummer, producer, bandleader, and label owner decided to collaborate with Appleton Estate Jamaica Rum on a project which fuses two of the island’s most celebrated exports. Touted as a new subscription service, Boyd has curated a limited edition ‘rum and jazz’ vinyl series, partnering with some of the scene’s brightest up and comers in Theon Cross, cktrl and Demae. Subscribers will receive unreleased tracks from the artists, influential Jamaican records of yesteryear and a premium blend cocktails as part of the deal to learn about the origins of some of the island’s most influential sounds.

The Jamaican Jazz Series is a whistle stop tour of the artists and songs that make up the jigsaw of the country’s musical history. “If you listen to a lot of Mento, a lot of Ska, a lot of the pioneers that went to the famed Alpha Boys School - Joe Harriott, Rico Rodriguez, Cedric Brooks who all later emigrated here - were all given that tutelage in Jamaica. They all influenced British jazz but also kept their own identity,” Boyd remarks.

The relentless beating heart of Jamaican jazz music has kept going strong throughout time, shapeshifting, warping and tweaking itself through various eras and iterations, whether through Count Ossie’s Rastafarian-influenced Nyabinghi drum patterns, King Tubby’s pioneering echoes and reverbs, or the party-centric keyboard riddims à la Vybz Kartel.

“Jamaica is such an interesting musical landscape to study because it's got its own thing, but then in talking to a lot of the elders, working with people like Vin Gordon, talking to my mentors and family that hail from Jamaica, as much as they were pioneers, they were also sponges as well,” Boyd says. “Jamaica is as much an innovator as it is a sponge. It’s a great sponge nation in taking things on and rinsing it and doing their own thing.”

Given its size and surrounding areas, the island undoubtedly relies heavily on neighbouring countries and movements, but the country has always kept its own distinct character over the decades gone by. That unique identity has been preserved fearlessly by all of the artists who so proudly wear Jamaica’s black, gold and green on their sleeves, including of course, the UK jazz polymath himself.

“Disco Devil” by Lee “Scratch” Perry

“I think the beautiful thing about Lee Scratch for me is that he was one of my favourite producers without me necessarily even knowing it. I was influenced by a lot of his music without realising he was the man behind the boards, whether it was songwriting, production - working with Bob Marley and the Wailers, working under Coxsone - I'm sure there's loads in music he's not even credited for.

“Even though he's a very eccentric character and he's hard to miss, ironically his music can sometimes go past you without you knowing. His early contributions are so important, but they're almost understated because they're so pioneering.

“It's only when you go back retrospectively, looking at it like, 'Oh my gosh, Lee was here, he was there, he was there,' - and I'm not even talking about his contributions to music and in terms of technology, what he did for Dub and how that transformed the world - I'm just talking purely as a musician, as an artist, as a creative.

“My dad used to play the Max Romeo version, but then as I got older and started getting records and digging and discovered Lee Scratch Perry behind it, it was one of those great full circle moments for me, which is why this song, and Lee himself are such big influences.

“I wouldn't call him a jazz musician, but I think all his music has such an improvisatory quality to it, whether he's behind the boards dubbing it, or the arrangements, or how he's put instruments together. It’s the rawness of it, it kind of reminds me of Thelonious Monk and listening to some of those guys that just have their own thing. It's like organised chaos, it's not that chaotic, but it's so beautifully abstract. It's sort of like listening to Cecil Taylor, it reminds me of that. And this was just from a guy from Clarendon in Jamaica, its beautiful.

“You could never replicate it - he is, and was - such a character. He added such a beauty and abstractness to Jamaican heritage, it's almost like he unlocked the cheat codes and just sat in the back for a minute, and then was like, ‘Nah, I've had enough of this, I need to be out front.’

“It’s quite interesting when you really listen to him and read his story. He really did the tutelage, and that reminds me a lot of how it is in Jazz. You just work under somebody, get with a band leader; him being around Coxsone and King Tubby and those guys in the studio, and then really getting this thing together, musically, technology-wise, putting his own boards together, making reverbs and delays back then - it's just incredible. What an incredible guy.”

“Sabebe” by Cedric IM Brooks & The Light of Saba

“He’s somebody who I discovered through six degrees of separation, weirdly. One of the other guys I picked - Count Ossie - Cedric Brooks was a saxophone player in the Mystic Revelation. I believe he was also part of the Alpha Boys School which was a famed orphanage in Jamaica that took kids of the streets of Kingston and surrounding parishes - and I only know it via folklore - but there was a famous nun that would use music as one of the disciplinary tools to keep the boys on the straight and narrow.

“From that school you've got so many incredible pioneers, Joe Harriott, Rico Rodriguez, Eddie Tan Tan, Vin Gordon who I played with, I'm pretty sure Cedric was one of them. I'm sure in Jamaica it's probably revered and talked about a lot, but I think there's a whole documentary in there that needs to be brought to light.

“What I like about Cedric Brooks is he borders the traditional. If you listen to this album Light of Saba, there's some incredible horn arrangements that make you think you're listening to Count Basie or something. But then at the same time, you've got this forward avantgarde-ness, a sheen across everything he does, that's like, "Okay, what was that? Were you listening to Ornette and Archie Shepp? Or did you develop this?" And there's a lot of unknowns, because he sadly passed before people could find out. People still don't know about this record and him as an artist.

“One of my mentors, Gary Crosby, was fortunate enough to tour with him. He was telling me stories about getting Cedric Brooks to tour with him in Jazz Jamaica, which was his band. It’s interesting having that full circle moment listening to Cedric Brooks. Hearing Coltrane and Ornette, as well as Basie, but then also knowing he was here in the UK working with my mentor or influencing the next generation of saxophone players here that I didn't get to play with; people like Nathaniel Facey, Jason Yarde, Denys Baptiste.

“I just wish he was more documented, talked about, more celebrated and more revered for the artist he was. What I like is that he came from the Count Ossie Mystic Revelation, which if you listen to it is like deep Nyabinghi, Rastafarian worship music, and he's always kept that within whatever he does. This particular track to me is a great example of Jamaica being as much an innovator as it is a sponge for Jazz at the same time. Everyone fames Jamaica for Reggae and Dancehall, but hopefully with this we can shine a light on some of the Jazz elements of Jamaica.

“I think this is a great song for anybody that loves jazz and doesn't know much about the history of Jamaican Jazz, just to see and hear all the elements going on at once. The arrangement, as well as the Rastafari Nyabinghi element, as well as the sort of avant-garde element in parts. I'd encourage anyone to just check out everything he's been a part of - it won't take you long. It's definitely worth it.”

“Slave Driver” by Dennis Brown

“This one again is obviously not a strict Jazz track, but to me, Dennis Brown is one of the world's greatest vocalists. It’s really his tone, I can't speak for the man, but I feel like he was definitely influenced by a lot of the Jazz crooners.

"Obviously, he took it in his own direction in the reggae world, but I love this song particularly because it's a Bob Marley tune, and it's just incredible to hear his take on it. It's not often that I'll hear a Bob Marley song done, in my opinion better than Bob Marley, but it's one of my tunes that I always go back to. So that's part of the reason I had to sneak it in here.

“This was actually introduced to me by my friend Nathaniel Cross, who's a trombone player. His Dad was in a lot of Reggae bands in London. I remember him one time being like, "You must have heard the Dennis brown version?" I think that's the beautiful thing about a lot of Jamaican music, you could have the same song in the same way with Jazz. You can hear Thelonious Monk playing "Round Midnight" and you can hear John Coltrane playing "Round Midnight," and have these different versions.

“I hadn't heard it, and he was like, "I actually prefer this to the original." And ever since that day it’s been one of those staples. The production of it is so tight and so strong and so solid, it's hard not to love.

“His best song? You know what? That might get me into trouble! It’s one of my favourites, that's what I would say. He holds a place in so many people's hearts, because if you go to any Jamaican function it's hard not to hear Dennis Brown over the sound system. He's such an important person to a lot of people, consciously or unconsciously, I'd hate to be like, 'Yeah this is definitely his best one!'”

“Mabrat (Passin Thru)” by Count Ossie and Mystic Revelation of Rastafari

“Count Ossie is an interesting character because he is drawing on a few different traditions at the same time. He's got the Nyabinghi influence, which is quite closely linked to the Rastafari movement and the call for back home and Africa. But it's also linked to the Maroon people, who are a people that basically fought the slave keepers and colonisers within Jamaica and fought for their freedom.

“They actually have their own town, their own flag, their own country within Jamaica, and as a result they kept a lot of their African traditions, languages, rituals and all sorts of things, it's quite pure. Even to this day you can go up, with permission, to see for yourself, and the drumming in particular is one thing you can hear as being very well preserved.

“I guess at the time you're merging philosophies - he's the bandleader that's drawn on this deeply spiritual element coming from Africa, but also settling within the culture of what's emerging in Jamaica. Then on the front of it it's almost got a small, big band-type aesthetic to it. There's parts of it you listen to and it sounds almost like Duke Ellington has arranged the horns. I'm always interested in what was going on at that time. You had all of this influence, but then the horns in parts sound like John Coltrane, as well as Count Basie and Duke Ellington.

“This tune in particular is a take on a tune from Fiddler on the Roof. Charles Lloyd also has a version of this called something else, so I don't think it's completely an original song but what I love again is that jazz thing - to take a show tune and do your own thing with it. Again, this is a perfect example of that beautiful synergy of culture meets an absorbing other culture, meets washing that and turning it into something else.

“I don't think there's an album I've heard that is as unique as this one. The Mystic Revelation of Rastafari is deeply religious and spiritual, but also deeply danceable, deeply moveable, deeply melodic, deeply jazz, deeply avant-garde, deeply singable, deeply teachable. There's so many things within this album, it's hard to pick one track.

“The Nyabinghi thing which underlines a lot of Count Ossie's music, which you hear again in Cedric Brooks, is a style of drumming synonymous with the Rastafari movement. There's a particular set of drums, and rhythms whose roots stem from West Africa. I had a conversation with Sampha and he believes it's from Sierra Leone, I've heard people say Ghana, Nigeria. It's probably hard to pinpoint exactly, but I think with the history of the Maroons it's fascinating, because that was the land they were taken from, and because they fought for their freedom, they were able to preserve their traditions and their culture. It's almost like a time capsule of enslaved Africans living in Jamaica independently, so their music is completely different.

“At the core of those rhythms, it's almost like a heartbeat. Then I think of Afrobeat, and music of the Diaspora, it's like that heartbeat is never lost. Knowing the history of the Maroons and where that music comes from, it's just a very important thing to me, being of Jamaican descent.

“This whole album, and everything else that Count Ossie has done, is such a brilliant example of the forward-thinkingness, the progressiveness of Jazz in Jamaica. It's not often you hear someone say that but it's all of that and more.”

“The Wrong Things” by The Congos

“I can't tell you how many times I've listened to this, it's just so beautiful. I think Lee Scratch even had a part in this album. The harmonies and the vocal style, it's in that falsetto register - it's hauntingly beautiful, because what they're talking about lyrically is quite deep.

“For me it's the perfect recipe, the vocals are beautiful, and again, it's not strictly Jazz but it’s got that thing where maybe they were even influenced by Doo Wop and those closed harmonies, as well as obviously hearing what Lee Scratch had done with Dub. The musicianship across the album Is great, and this whole album Heart of the Congos is beautiful and a testament to that thing. Although we know Jamaica for Reggae, they were also a great sponge nation in taking things on, rinsing it and doing their own thing with it.

“I got into this one quite late, actually. I was aware of The Congos, they've had a few big hits like “Fishermen,” and a few songs they're really known for, this one you don't hear that often but it's a beautiful piece of music. I think this one is a good example in the way it's arranged, the way it's put together, the melody, the harmony. It’s drawing on so many things for me, not just Jazz.

“It's quite funny, because it's slyly cussing Christianity, "Every day my people go to church, yet the living seems worser than worse / They talk about Marcus Garvey's prophecy but they don't know their own history." So I'm imagining being in Jamaica, when Rastafari is blowing up and this song is cussing part of the Church, part of Rasta, which art should do. Art should be able to be a commentary.

“People could take offence if they want, but you should have that freedom to speak on these things. This song is almost doing that, but it's disguised so beautifully. You could just listen to it and not almost feel what's happening. But when you really focus on it, it's like 'No, this is a real deep song.'”

“Wall Street” by Jackie Mittoo

“I came across this record a couple years ago. I didn't know about this one, but I'd worked with people that had worked with Jackie Mittoo so it made me think to check him out.

“You know when you listen to an album and there's one track that's just like, 'Whoa, wait a second?' I love it, I love it, I love it. It's so good, it's almost indefinable. It's one of those tracks where I wish I could shout from the mountaintops about this, like 'Have you heard this song?! Do you know this song? Do you know this exists? Did you know this came from Jamaica from one of the most prolific session musicians of all time?!'

“Jackie Mitoo was a famous keys / organ player, arranger and composer. I think he was most associated with the Studio One house bands, so he would have been behind pretty much anyone that was passing through during the heyday.

“If you had released this song on a Strata-East label or a CTI or an Impulse thing in the ‘60s, you could pass it off as maybe a Lonnie Liston offshoot track, or maybe a Herbie Visits Jamaica. It's so ahead of its time, from the production, to the style. It's got that element of the Nyabinghi pulse, but it's also got this almost Mento thing going on, which is another style which was around the Calypso / Ska era. It's got all of that, but it's slow and its sensual, it's beautiful and it's lush and it could almost fit into the spiritual jazz movement, but it's not - it's coming straight from Kingston.

“Not much really happens in the song, but it’s so enchanting you can't stop listening to it. Again, that's something that I love about the Nyabinghi drumming, it’s like these rhythms that just repeat again and again, but the way he's done it with a Fender Rhodes and the bass, it's just so good man.”

“Midnight Ravers” by Bob Marley and The Wailers

“I picked this one, and I particularly made sure I picked the original version, because I got to work with Tony Platt, who is a famous mix engineer and producer, who worked on this album. One thing he was telling me was that The Wailers kind of already had the album ready, but they wanted to crossover. So his job was to help add the overdubs, and almost westernise the song.

“So for me, I grew up hearing the commercial version which is great - it's a great album, but then years later I discovered the original Jamaican tapes which they released. And I'd implore anybody to listen to what you've heard, and then listen to this, and just see what these guys we're actually doing and dealing with before they got to England.

"Midnight Ravers" is an interesting song because when you listen to it, when you're given the context - I was given the context by one of my mentors - this was when Bob Marley had obviously come to England for work with Island and Tony Platt, and he's hanging around in Soho and in Piccadilly Circus where a lot of Jazz is, and all the Jazz clubs and spots were at that time. And obviously he's of the lens of a Jamaican man coming to England not understanding what's going on; the first lyric is, “Can't tell the woman from the man.” You couldn't really say that nowadays but it's just so interesting - it's not often you get a snapshot into someone's true reality, “Because they're dressed in the same pollution their mind is confused.”

“The song is about people going out in London, and the madness that he's probably seeing. Just hearing how he translated that, but still sounding like it's coming from the depths of Trench Town. Again, it's not a particularly Jazzy track but there's something beautiful about, for me, the arrangement, the songwriting, the intent, and just the pure, raw emotion.

“Often with Bob Marley everybody loves “Three Little Birds” or “Is This Love,” but I think he's got some songs we also really need to listen to and take note of, to hear the other side of his story, and this is one of my favourites.

“I grew up listening to this album, but the other version. So it was important to highlight that there is depth to these artists and there's other versions that we may never hear, but fortunately we get to hear the raw version of what the Wailers were dealing with that that time. What a beautiful track.”

“Stop Them Jah” by King Tubby and Augustus Pablo

“I thought I couldn't leave this list without some sort of Dub, although Lee Scratch kind of touches on it. This is another just pure Dub track, but taking a lot of jazzy elements, and Augustus Pablo’s improvising in his own way, with his own songbook and as a musician. That marriage between producer and musician has always existed so strongly in Jamaican music and particularly Jazz-influenced Jamaican music.

“I could have picked a million examples, but this was one of those tracks that’s a great illustrative example. It features Augusto Pablo, who probably made the melodica famous and King Tubby is also another contemporary of Lee Scratch Perry, and though not strictly a Jazz musician I think what he was doing in the Dub world was largely improvisatory.

“This track in particular is quite interesting with the horns in the arrangement. It's interesting how much that can carry a song, or did carry a song, back then. Augustus Pablo isn't the singer really, but the way they use brass to carry melodies and utilise those elements - that never really died.

“If you listen to Count Ossie, who I mentioned earlier, right up into Mento, into Ska, right up into Calypso, right up into Reggae, I'm sure those elements of instrumentation were influenced by the big bands, the swing bands of the time. That has never died, it's always recontextualized.”

“Slow Motion” by Vybz Kartel

“For me, he's one of the most prolific artists to come out of Jamaica. After talking about all of this music, listen to this song again because it's so musical. I know he's chatting about 'gyal' but so what? So was Bob Marley!

“It's musical from the first note, the chord, the horns - even though they're synthesised horns - it’s actually a really well-arranged song when you really listen to it. If I were to transcribe that for an acoustic instrument, I could pass it off as a Duke arrangement or Count Basie arrangement. The way the horns enter, it’s obviously him, and I'm almost imagining him being at the front of a Big Band, it's really sensual and almost like a crooner how he starts, right?

“The melody is beautiful; it almost sounds like he's trying to be a horn. The thing for me when the song drops is the biggest curveball, it sounds like Kwaito music from South Africa. Kwaito is a style where the legend has it, a lot of dance 12"s, made their way to South Africa but they didn't realise you had to play them at 45RPM. So they played them at 33RPM, which created a whole genre of low fi dance, rappers, singers, all sorts, and it's beautiful, it’s incredible.

“This tune is interesting, because if you really break it down I don't know if it's even fair to call it a dancehall tune, because the drum beat is this weird Kwaito thing, which maybe you can call a recontextualization of Calypso maybe, who knows? But to me it's more something else. Then you've got these synthesised horns that sound like they're trying to be Don Drummond as well as Count Basie, and then in the dead centre you got the World Boss himself.

“It is a bit of a curveball track, and you can take it on face value and just enjoy the song, but when you really actually start to break it down - even the fact that it's only two minutes long, it reminds me of those old 78 RPMs - that’s it, this is the arrangement. It's 1 minute 59, but it slaps so hard! I'm always curious why he made it so short, but the song is beautiful.

“I've always had this thing with Dancehall where I know a lot of the music, but I don't. You know when you're in the dance and you know the song, but you couldn't say who it is? That's kinda like me with Vybz. I know it’s Vybz Kartel and he's got so many tunes that I know, but I couldn't tell you what they're called, but this is one, the minute I heard it, I was like, 'Wait, this is special.'

“I love everything about this, which is maybe a curveball to some people - it's like ‘Don't shoot the messenger, listen to the message.’ Even though he's playing these horns on a keyboard, listen to what he's actually done with them. Whoever produced this has really thought about this as an arrangement, which I think is quite deep.

“I can tell he stands on the shoulders of that tradition of Count Ossie, of Don Drummond, of The Skatalites, of Lee Scratch, of King Tubby, of Bob Marley. They've never lost that within it all, this is just the new iteration.”

Moses Boyd's Jamaican Jazz Series Box 3 featuring Theon Cross is out now

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Patrick Wolf

Crying The Neck