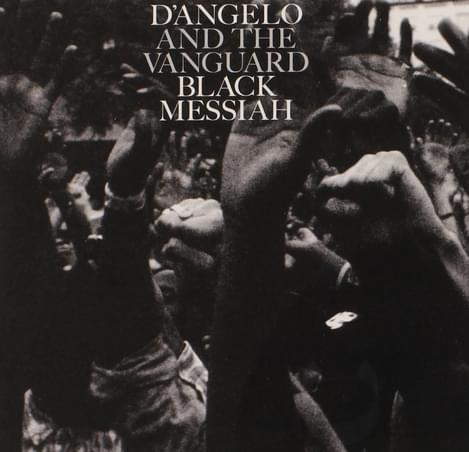

D’Angelo - Black Messiah

"Black Messiah"

The intervening years were strange for D’Angelo: he had some brief and bizarre run-ins with the law; he experienced a near fatal car accident in 2005 (fucked up on booze and cocaine he flipped his Hummer off the road and stuck it into a fence in the middle of Virginia one night, breaking every rib on his left side in the process); he was twice in and out of rehab struggling with drink and drug addiction, and at least appeared to be suffering from a case of chronic writers block, among other things. And so, the beginning of the new century – the Internet, two American-led wars, a black president, the capitulation of hope and an entire Kanye West discography - happened in D’Angelo’s notable absence.

With this in mind, D’Angelo could have been forgiven for making an album that comes off somewhat confused about its place or purpose in the modern world, either straining to play catch up or limp with nostalgia. Except it’s neither of these things. Black Messiah is emphatic; it’s pertinently weird and beautiful and possessed; its rage is masterfully concentrated, its critique is devastatingly pointed.

Black Messiah wasn’t supposed to drop in 2014. It turns out D’Angelo rushed the release date in response to the nationwide protests and rioting sparked by a grand jury’s failure to indict officer Darren Wilson for shooting dead Michael Brown in Ferguson earlier this year - which lends Black Messiah, an album that is really a decade and a half overdue, the feeling of in fact being right on cue. On “The Charade”, D’Angelo reflects on the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement and deconstructs the notion of a “post-racial” American society. The charade is, among other things, the judicial system, the law, the police force, the Obama administration; the charade is the very idea of America and its infinite star-spangled possibilities. On the hook, in a solemn, muffled drawl barely legible underneath the cacophony of droning guitars and sharp snare licks which appear at times to imitate the cracks and bangs of live ammunition, D’Angelo sings: “All we wanted was a chance to talk/’stead we only got outlined in chalk/Feet have bled a million miles we’ve walked/Revealing at the end of the day, the charade”. There’s more anger and distortion on “1,000 Deaths”, where D’Angelo and The Vanguard break out into pure destructive abstraction - funk derailed, vocals drowned in noise. “1,000 Deaths” is the negative imprint of the “The Charade”, a simmering, brutal and industrial assault against the charade. The explosive, nightmarish close to the track recalls the freakish clamour that breaks out in Eugene McDaniel’s protest song, “The Parasite (For Buffy)”. It’s the sound of American cities burning: “It’s War/That is the Law!” There’s a sense of instability, a barely contained chaos, twitching and reverberating across tracks like “1,000 Deaths”: the wild intensity of the crowd; the multitude choked by thick walls of tear gas, clenched fists and picket signs piercing through poison smoke.

Not everything on Black Messiah is so fiercely charged with socio-political commentary. However, that doesn’t mean it necessarily fades; rather, it assumes a different form altogether. D’Angelo cultivates a space - a sonic ‘landscape’, to use his words – in which the particular and the universal bleed imperceptibly into one another, so that it’s hard to dissociate the private, individual body from the collective, social body and vice versa. If sections of Black Messiah are about scenes of protest and riot, others might well about fucking against the backdrop of a riot. Solidarity and struggle form the two main overarching themes on Black Messiah; D’Angelo made this clear enough in the album’s liner notes. But they’re themes D’Angelo and The Vanguard weave intricately into the leather tight fabric of what are ostensibly inward looking love songs (the flamenco-inspired “Really Love” and “Betray My Heart”, for example): What’s love without the struggle and the ugliness; what’s solidarity without love and empathy? Etc. etc. There is often even a nice duality at play in D’Angelo’s lyricism, a sort of narrative entanglement. On the track “Till It’s Done (Tutu)”, he addresses the collective on issues like global warming through what appears to be an intimate exchange between two estranged lovers: “Do we even know what we’re fighting for?” D’Angelo sings, “Destinies crippled and thrown about on the floor”. “It’s [Black Messiah] about all of us”, D’Angelo writes in the liner notes. In this sense, Black Messiah is about the search between bodies for a true collective, social body; it’s about the need to reestablish a type of connection that has absolutely nothing to do with technology and everything to do with people.

However, it’s the instrumentation and D’Angelo’s vocal performance that really steal the album. Musically Black Messiah sort of unfurls itself, drip by drip, seductively, inexorably, at the point where the violent meets the sublime, the destructive meets the ecstatic. It flows like a sheet of bubbling, molten hot lava, moving slowly and implacably across the landscape. Technically, it’s a near alchemic distillation of arrangements and textures, complex patterns and compositions, plucked from an array of genres and recalling decades of music history: Sly and the Family Stone, Curtis Mayfield, Funkadelic and Eddie Hazel’s “Maggot Brain”, Prince, Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill, J Dilla, and perhaps even shades of Yeezus. At times, D’Angelo’s vocals are lucid and delightfully crisp, delving confidently into vintage soul and funk on tracks like "Sugar Daddy"; at other times, it’s submerged by surging waves of feedback or battered by an aggressive hailstorm of percussion. On the "Prayer", D’Angelo’s sings a kind of drunken, woozy lament, pounded by thudding drum sequences and backed by sparse bells tolling omens of grave portent. D’Angelo whistles his way through “The Door”, a blues inspired piece inflected with the lazy twang of guitar slides: it’s rocking chairs, spittoons, and ceiling fans; it’s the stroke of midnight...It’s eternally the stroke of midnight on Black Messiah.

Given how immaculate this album is, it would be nice to hear from D’Angelo more often. But then again, in an age and an industry that demands a consistent, uninterrupted outflow of product, there’s something decidedly refreshing about his jangled hiatus, self-imposed exile, or whatever it is you want to call it. Black Messiah is an album totally devoid of gimmicks and there was no orchestrated hype in the build up to its unexpected release - no videos, no singles, and minimal publicity. This thing generated its own buzz. Black Messiah is quite clearly the result of years of patient and meticulous refinement, when D’Angelo had seemingly all but disappeared from music. D’Angelo dealt with his demons outside of the limelight, at his own pace and on his own terms, and you can feel them being exorcised and cast out all over Black Messiah. Yes, fourteen years is a long time to wait between records. But, when the end product is this good, it might just be worth the wait. D’Angelo might even allude to it himself: “Can't snatch the meat out of the lioness' mouth/Sometimes you ‘gotta/Just ease it out”.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Gwenno

Utopia

KOKOROKO

Tuff Times Never Last

Kesha

.