A good story or a good life?

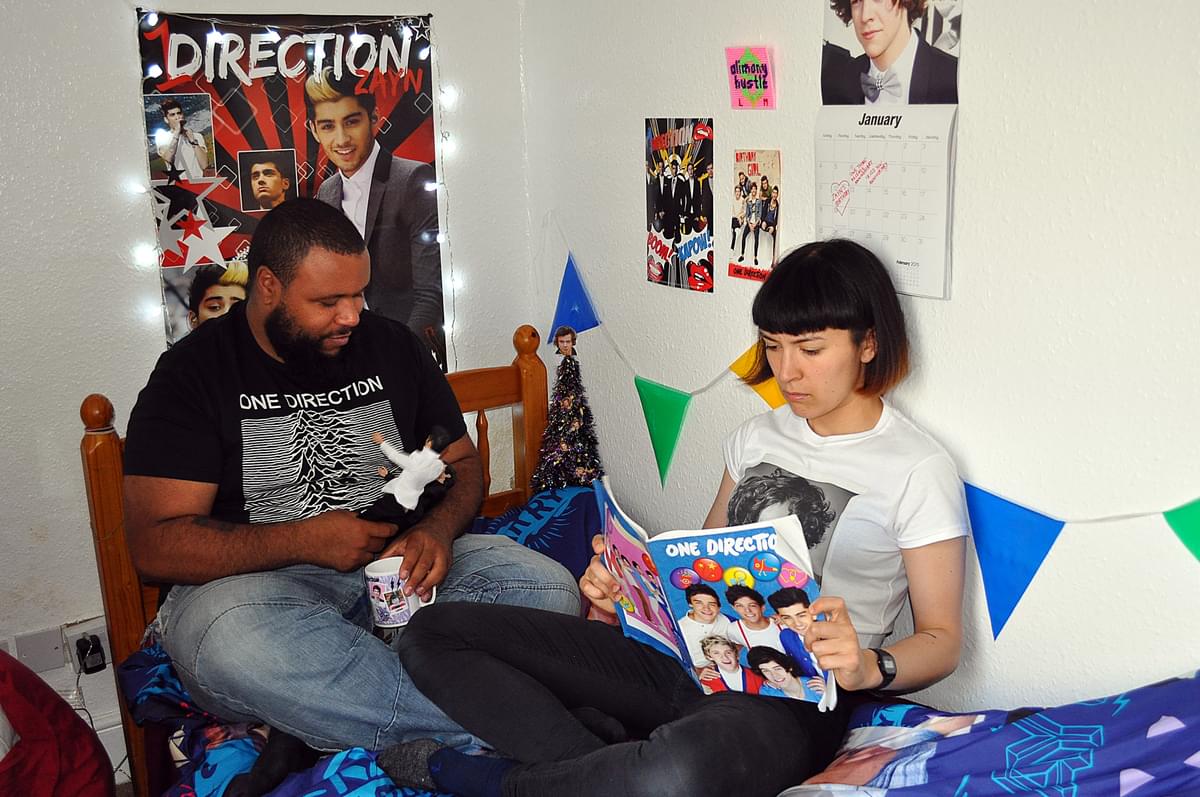

Musician Leah Pritchard - who plays in Alimony Hustle - has joined with food writer Ruby Tandoh to publish a zine about mental health. She writes below about her experience of depression with contributions from White Hinterland’s Casey Dienel and Joe D’Agostino of Cymbals Eat Guitars.

When I was 18, leaving my mum and sister in the Netherlands to come to university over here, I had huge visions for what I thought would be a rich, cultured few years.

I’d chosen Bristol purely based on the gig listings and because I thought PJ Harvey was from there (this is not correct). I had never visited or even looked through the course outline for my economics degree. In truth, I was depressed. I’d been depressed for a few years. When I look back, I can see that I had been neglecting myself terribly. I threw myself into the scary unknown, not because it was a fun adventure that I was ready for, but because I did not give a shit where I ended up. I just desperately wanted something – anything – different. I spent the next year drinking heavily, eating a 400g bar of Dairy Milk every single day, and staying in bed to watch Buffy the Vampire Slayer instead of attending any lectures. It was an awful year. When May rolled around, I failed most of my exams and had to drop out.

Much like Ellis Jones from Trust Fund - who explores the complicated link between depression and creativity in an essay for Do What You Want - I’d always thought surrendering yourself to your demons was the ultimate artistic sacrifice. I thought that at the end of of a period of alcohol abuse, weeping and self-harm, I’d emerge like a phoenix with a Grammy award-winning album and perfect mental health – healed by my own incredible art. I grew up listening to Elliott Smith and Jeff Buckley, and there wasn’t much nuance to the conversations around their music: I understood that they were sad ("depressed", though I didn’t know what that meant), they wrote beautiful music, and then they died. I thought "depressed" was a synonym for "extra sad" – the kind of sad that made you a wonderful artist. I saw their deaths as tragic, but I also longed to be martyred for my art.

Of course I didn’t write a single song during that period of clinical depression – an illness, I now know – not just a nebulous ‘sadness’, but continuous hopelessness, lack of motivation, anxiety and low self-esteem. I also didn’t seek any help. I didn’t know there was help for this. I thought I was just bad, lazy and broken and, having absorbed the message that depression is what makes the greatest artists, I thought I’d just wait it out, that my Either/Or was surely forthcoming. Recently, I spoke to Casey Dienel of White Hinterland about her experiences with depression, and saw that message come through loud and clear in her words, too: “I believed tampering with my mind would mess with something sacred to me. I was superstitious to anger the gods.”

For Dienel, if she was having a productive creative period, all else went out the window. She’d ghost on dinner plans, stay up all night – even if this meant having a panic attack the next day – and let her mental wellbeing fall by the wayside. For ten years, this cycle continued, until she had no choice but to take action. Her stage fright could no longer be tamed by a few gin and tonics and her insomnia had become “so routine that [she] could count down to the hour [her] next panic attack.” Bad spells that had previously passed in an hour now knocked her out for several days. She would stay in bed just to focus on her breathing. “I found myself wanting to silence all the noise in my skull not because I was ambivalent to living but out of sheer exhaustion.” All of her remaining energy was spent trying to act like she was OK. She cracked.

When Dienel was 28, she moved back in with her parents. It was a “humbling, three-year-long process to get back to emotional ground zero, kicking and screaming the whole way until one day I noticed I hadn’t had an episode in a month,” she explained to me. She exercised, went to bed earlier, ate differently, and saw a therapist several days a week. She got through six months. And then she relapsed. She asked her therapist what was wrong with her, and if it would always be like this. The therapist said the only answer was to keep her commitment to mental health. “Stick to what’s working. Be honest with yourself and those around you. Maybe tell your muse that sleep is more important than her, but let her know you have faith that she’ll be able to visit you during your office hours.” Dienel now has a consistent routine – with breaks and meals and bedtimes – when she’s writing and recording, which affords her “the climate to be weird and wild in [her] work.” She says for years, “[she] thought my life needed to be a good story in order to write. Now I think in order to write a story I need a good life.”

For me, depression is often about a failure of communication. When I am depressed, I feel as though I have no ‘craic’. I think about this word craic a lot. My friends in Durham say it – a less divisive alternative to ‘banter’. It's perhaps easier to define it in the negative: we talk about people who are nice but boring as having ‘no craic’. Depression, for me, is having no craic. It is a time when the good and funny thoughts just aren’t coming – my brain has stopped making them, or has stopped sending them to me. I am in a different gear to the people around me, and I feel guilty for them having to talk to me, and for them having to engage with someone who is giving nothing back. [Extracts from Ellis Jones' piece for Do What You Want.]

There is a practical element to my music obsession that I often overlook. Yes, I wanted that toy keyboard when I was nine because the melodies to S Club 7’s "Reach" had touched my tiny heart, but I also channeled a lot of my hyperactivity and anxious behaviours into my new hobby. Many people suffering from an anxiety disorder, or obsessive compulsive disorder, experience symptoms like counting, ordering and arranging, or repeating words in their head. Some will obsessively pick their skin, bite their nails or grind their teeth. For me, I could channel my need for order and repetition by learning mathsy music theory, and distract myself from my physical compulsions by placing my hands on the keys. Instead of repetitively knocking, like they would if I let them rest on the table, my hands would be guided up and down the keyboard by the chords and melodies that sounded good. It was easy to give up this obsessive control of my body if something beautiful could come out of it.

When I talked to Joseph D’Agostino, singer and guitarist for Cymbals Eat Guitars, it turns out he experienced something similar: “As a child I would repeat the same string of curse words in my head for hours – sometimes days – like a warped mantra.” At secondary school, D’Agostino was bullied. He would “compose stinging rebukes for [his] perceived enemies and silently rehearse them until they were pitch perfect, but never let them fly.” As it does for many, this bullying had a huge effect on his self-esteem. He turned his own anger inward. He would repeat, "You should fucking kill yourself, piece of shit" over and over. As recently as four or five years ago, this mantra still surfaced.

As I did when I watched Buffy the Vampire Slayer on repeat for days, D’Agostino began to dissociate by playing video games. Dissociation is a symptom of a lot of mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, and consists of feeling disconnected in some way from the world around you or from yourself. For Joe, me, and many others, ‘disappearing’ into music, video games or TV, is an effective way to – as D’Agostino puts it – “break the cycle of negativity”. It can function as a short-term way to switch off from stressful situations. If you dissociate for a long time, especially when you’re young, this can develop into a dissociative disorder, where you dissociate frequently, possibly for long periods, and it may become the main way you deal with any stressful situations.

When D’Agostino was 13, he took up guitar: “If I spent all my free time thinking about a song I was writing – revising lyrics, imagining different arrangements, composing harmonies and keyboard parts – there was no RAM left for negativity and self-flagellation.” When he listens to the first Cymbals Eat Guitars album, Why There Are Mountains, he can remember the untold hours and days and weeks he spent writing each bassline, drum hook and guitar solo: “they seem like their own little gifts now, antidotes for blank misery, purposelessness, and loneliness.” For D’Agostino, it’s not as simple as mental illness being ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for his music. “This is the only reality I've ever known,” he says. Making music is his way of managing his obsessive behaviours, for staying present instead of dissociating.

For Ellis Jones, coming off the medication prescribed for his illness left him flailing, and uncreative. For Dienel, seeking out mental health treatment – and making a lifetime commitment to the care she needs – is what makes her music possible. For D’Agostino, music is the best way he knows how to channel the maladaptive coping mechanisms he developed as a bullied teenager. Clearly the link between music and mental illness is not as simple as the stories about the ‘tortured geniuses’ would have us believe.

Not being able to do something you love is frustrating. I feel that frustration keenly when I'm depressed. It often leads me to be less open to other people’s music, and critical of the music “scene” in general. It makes me bitter and selfish. Over time – I have been writing songs for maybe fifteen years – I have, hopefully, got a little bit better at dealing with this. Realising that this lonely, depressed, pessimistic place isn't where I'll make my best music has helped me to weather the storm. I can sit back; I can take the time to heal. [Extract from Ellis Jones' piece for Do What You Want]

For me, my most recent song didn’t come to me in the middle of the night while I was struggling to sleep, or after I’d sunk four beers in a row. It didn’t come during a period of depression – which usually means I can barely string together a sentence for an email, let alone lyrics. It came when I was doing OK – not great, but OK – and had enough energy within me to sit at a desk, pull out my guitar and try something. It came after I’d really opened up to my friends and to my partner, and sought counselling, and waded through my muddled thoughts and feelings to see that writing music is something I really want to do. When I gave up writing after 30 seconds, my girlfriend came in and told me to try again. After a few weeks, and a lot of tears, I had a song, almost two years after I’d written the last one.

Only you, with the appropriate support and healthcare, can work out what’s best for you – what feels healthy and sustainable for your body and your soul. All I know is that I choose to believe Casey when she says: “You don’t have to choose a good story over a good life. You can, and deserve to, have both.”

Do What You Want features pieces by Ask Polly’s Heather Havrilesky; interviews with Mara Wilson and Sara Quin; recipes from Diana Henry, Tejal Rao and Ruby Tandoh; and a poem by Lan McArdle (formerly of Joanna Gruesome). Profits are split between Mind, Beat, Sisters Uncut, Centre for Mental Health and more.

Pre-order Do What You Want at dowhatyouwantzine.co.uk.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Gwenno

Utopia

KOKOROKO

Tuff Times Never Last

Kesha

.