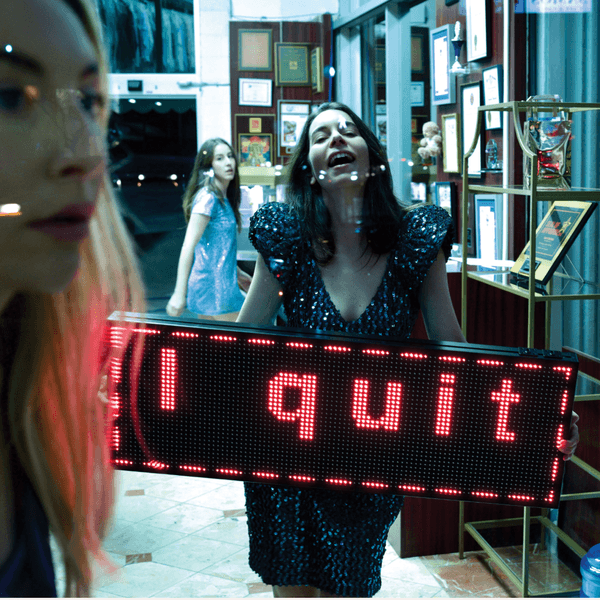

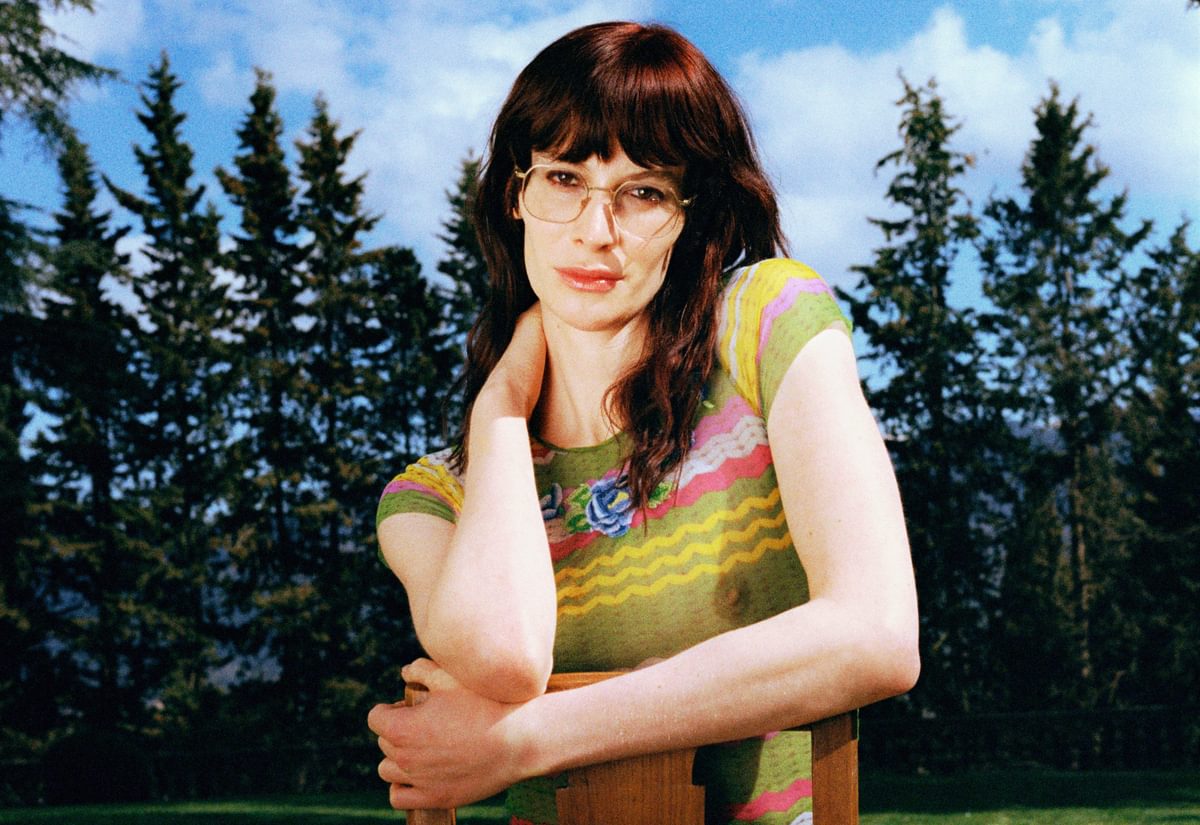

Lyra Pramuk is against interpretation

Lyra Pramuk makes music designed to both confound and connect. Her experiential new album Hymnal is part of a wider ambition to shape a less consumerist musical future away from the algorithms, as she tells Samuel Cox.

In 1739, a French inventor called Jacques de Vaucanson presented to the public the Canard Digérateur, an automaton in the form of a duck.

The mechanical duck could, without any human intervention, flap its wings, move its beak, eat kernels of grain, and duly turn them into waste. Even more uncannily, one of de Vaucanson’s less well-known inventions – the Flute Player – was a machine in the form of a human being which played the flute via an artificial breath the inventor had conjured using a series of bellows and pipes. The mechanical flautist, by all accounts, played beautifully.

De Vaucanson’s flautist is only the most novel example of technology and music’s long symbiosis, from music boxes to automated bell-ringing. Lyra Pramuk, whose second album Hymnal seeks to combine the musical possibilities of nascent technology with music’s more atavistic, communal folk traditions, is conscious that her music, while boundary-pushing in so many ways, is part of a lineage that predates even recorded music. “Even before electronic music there was a lot of music technology,” she explains, recalling a recent visit to “a really cool museum” in Utrecht that’s home to a collection of automated musical instruments.

“Most of them are manual organs, a lot of self-playing instruments, which was a whole culture for many, many years,” she says. “One of the earliest ones they have is this Dutch carillon that was used to sound the hour. It was just mechanical, without electricity, and it would run on its own. The village would have this mechanical, technological, sonic instrument that would steward them through the day. I think technology has always been a part of music and so if you take that as fact – that everything is technology – then you can kind of choose the aesthetic process of the technology that you use in music. Technology can be a medium [and] an aesthetic.”

Pramuk doesn’t see the technological side of music as something which makes it inherently less human, either. “Technology, I think, is an extension of us,” she says. “We invent technology, it’s not a separate thing.” To illustrate this, she uses the example of a shoe. “We imagined we could have a shoe that would allow us to walk further and protect our feet. We made it and it became moulded to our body to the point that, thousands of years later, our feet actually changed shape, because of the shoe that we designed. So technology is something that we imagine, that we create, that extends our perception, but also that shapes us in some way.”

The same principle extends to the digital landscape we live in, she says. “We are intermingled with it, we are in process with it, we are being moulded with it. We imagine it, but then it shapes us. So we need it, actually, to tell stories about who we are in this time. In this very technologically-mediated time, how can you not have folk music that has technology in it?”

Much like Todd Rundgren’s A Cappella and Björk’s Medúlla before it, Pramuk’s 2020 debut Fountain was an album created entirely using the human voice – specifically her own, which she honed both in Pennsylvania church choirs as a child and, later, at the Eastman School of Music in upstate New York. Like both those landmark albums, Fountain employed electronic manipulation to texture and shape Pramuk’s voice, to make it less (or, rather, more) than human. Like her shoe analogy, Fountain imagined a future in which the human and the digital had become enmeshed, in which the vocal cords – like our feet – had changed shape.

On Hymnal, Pramuk still juggles the organic and the artificial, the two becoming an indistinct blur, but instead of looking within she now looks with-out. “Fountain felt more personal for me,” she says. “I spent a lot more time when I was conceptualising and producing that project just thinking about what I needed in that moment. I feel stronger now, more sure of myself. So Hymnal is more like ‘Okay, this world felt good to me, but how do I go forward with this? What is a more collective, political philosophy around my work? How does my work hold other people?’ And I was struggling with that question for a while, actually, because it’s very complicated.”

One way Pramuk has sought to answer this question on Hymnal is by bringing other musicians into her work, allowing her voice to flourish alongside orchestration, with voice and strings becoming barely distinguishable. As well as working with arranger Francesca Verga, the album features the strings of improvisation-led Berlin musicians Sonar Quartett. “They are just phenomenal musicians in their own right,” she says of their two-day recording session together.

“There was a lot of stuff that was improvised by them, so their voices are really across the record. It’s possible in classical music culture that vocalists think that they’re more important than instrumentalists, but I never did. It’s really important to me when I write music for instrumentalists to really consider their agency, their experience, their knowledge, and their background – and to engage with musicians as artisans, as artists, so I think that really comes across on the record.”

This democratic approach to collaboration springs from the fact that, for Pramuk, music is in essence a communal activity. She talks of “really remembering, really committing, to music as a healing, medicinal practice” and of music “as a tool for storytelling [and] community-building.” Just as she is conscious that her melding of music and technology has its historical roots, so too is she aware of the precedent for music to be a cooperative activity, rather than mere product.

“Throughout most of human history, music was a social good and a commons,” she says. “It no longer is, I’m reminding you now. So maybe these big pop festival shows and huge, big-money corporate dance festivals are not the centre of music culture, [and] maybe that is more of a deviation from the norm throughout human history.” In a summer in which London’s Brockwell Park has become the site of an embittered battle between commercial festival organisers and local residents who feel physically and financially excluded from their local green spaces, the possibility that music could be a tool for community-building rather than merely a corporate enterprise is one Pramuk is likely not alone in coveting.

Another way Pramuk has endeavoured to answer her own question, “How does my work hold other people?,” is by launching a record label and self-described ‘experimental hub’, pop.soil. “I felt a need for my music to be more of a space that people can walk into,” she says of the venture, described on her website as a project that “cultivates adventurous new musical forms and fosters a diverse, dynamic artistic community.”

The hub includes digital content, workshops, performances, and a residency on NTS Radio. Hymnal, Pramuk says, “is very connected with the need for me to start my own platform,” but, if anything, she sees pop.soil as a greater culmination of her musical philosophy. For her, the album format is more of a functional undertaking, done in order to appease and to continue participating in the industry at large, rather than the epitome of her artistic practice.

“To be frank, the music economy forces me to lead with a piece of recorded music,” she says. “In a way, that’s how the whole industry works. There’s a part of me that would love to build a performed music practice with others and just take that on tour before even having to record it. I think I’ve made it clear already that I think music is much more than the recorded artefact of music. But if I need to do this then I want it to be useful and accessible. I think about it like it’s a piece of furniture, almost. It’s like a sculpture or a material.”

Thinking of Hymnal as a piece of furniture, you'd be forgiven for expecting it to be practical, necessary, but ultimately utilitarian. In reality, it is anything but. Despite her scepticism towards the format, Pramuk’s new album masters it and uses it to conjure an entire world of her own making, just as she had on Fountain. It does not, simply put, lack ambition or scale.

“I did the vocal recording session in a friend-of-a-friend’s place – a home studio in a really tiny village in the middle of the Dolomites, under these gigantic UNESCO-protected mountains,” she says. “It is very different to use my voice in that space, rather than in Berlin. When you’re in a village in nature like that, people use sound so differently. It’s a smaller community so you don’t have this competition of noise. I didn’t write any vocal parts on the record, it was just improvising [and] I can still hear how that location coloured the style of the improv. The mountains are so overpowering that you feel actually quite small in that space, so there’s a lot of smallness in the way that I was performing that is unusual for me. Normally I try and rise above the chaos of Berlin.”

Another session, in Venice, had a similarly profound effect on the album: “I had done a residency in this cathedral space in a very quiet part of Venice. I got to know the church, the reverb, how it felt for my voice. I had worked on some early demos there even two years prior. I didn’t actually record live vocals there [for the album] but we set up a re-amping system there, and then from the Dolomites session I re-amped one-third of the vocals into the space. In several places on the record, I used the reverb from that space, so [it’s] really part of the record in this very organic way.”

"I want to make music that feels like a new language, really raw and different."

The vocals, though no longer taking centre stage in quite as bold a way as on Fountain, are still very much the central instrument on Hymnal. On “Solace”, single-syllable vocalisations pulse like Steve Reich strings and mallet percussion, while on “Babel” disembodied voices are pulled, stretched, and manipulated to near-breaking point. Most strikingly of all, on the majestic “Meridian”, Pramuk’s voice stutters, stammers, mispronounces, and repeats itself, its bucolic poetry about sun and soil barely elocuted. It’s hard to miss the fact that, on Hymnal, language is ambiguous and fallible.

“I knew I wanted to bring more language in from my last record but to really build a process around it that was more deconstructed, [where] language would not centre so much,” says Pramuk. “For me it’s important to fracture language so you can consider sound as a medium, and listening to music as an experience. I follow Susan Sontag’s logic when she was writing about having a subjective, somatic experience with art rather than trying to interpret it or intellectualise it.

“I think the way we now consume information has become so depersonalised and without emotion. With most pop music, I feel people can just shut off their brain and consume this story that someone is giving them, so it really becomes about the artist. I think that by fracturing language, it allows two things to happen. One, that these fragments of language become this third thing between me and the audience, where they also have to interact with it and consider it for themselves. Two, I think that with more deconstructed, fracturing of language, the music itself becomes more of a language that has to be understood and felt. I find it allows the music to speak more as its own kind of logic. When you have a lot of text, people pay less attention to the symbolic, emotional, linguistic nature of music itself. So I think having fewer words, or fractured words, allows music to speak as well.”

She adds that, “On another level, I think I try to mirror back the world a bit in my music, and I think most people are stuttering. And so it’s an aesthetic reflection of our disconnection from our true, authentic core and emotions with the Earth and with each other. This stuttering is really a perfect depiction of the state of so many of our souls. It feels more authentic to me than writing normal lyrics or writing ‘Oh, everybody is so disconnected from themselves.’ It’s like, no, feel it. Here’s the disconnection. I’m not even going to give you a whole sentence.”

While Pramuk may only give us fractions to work with, keeping us in a state of guesswork, Hymnal is without a doubt an album with an eloquent and decisive agenda. “Going back to the fracturing of my music or the weirdness of my music, I think it’s very much a response to this time we’re in,” she says. “I consider the aesthetic of my work to be a disruption of algorithmic protocols for songwriting. I want it to be weird, I want it to be deconstructed, I want it to be a kind of viral counterpoint to the dominant narrative, which is just, ‘Oh, we can write our own songs in this and this style and people will just want to consume it.’

“I want to make music that feels like a new language, really raw and different. Some people might connect to it more and then those people might – just might – possibly think, ‘I like this music better than this 1970s-style rock drivel that these companies are producing with algorithms.’ And then maybe people won’t want to produce it as much, if more artists are making much more experimental forms of music that shifts music culture. A camp of young avant-garde artists who are making anti-algorithmic music, music that seeks to continually avoid and subvert algorithmic protocols – that’s where I’m putting my flag in the soil right now. I want to try to outrun it, aesthetically.”

On Hymnal, Pramuk certainly does outrun dominant and conventional narratives around music. She laps them several times over, in fact. It's an album that takes the human and makes it digital, and takes the digital and makes it human. Jacques de Vaucanson’s mechanical flautist may seem uncanny at first, an automaton making human sounds, but in actuality his inventions were feats of human creativity. Hymnal, for all its post-human aesthetics, is a testament to that same imagination.

Hymnal is out now via pop.soil/k7!. Lyra Pramuk plays Manchester and London in September. Tickets are available here.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex

Loyle Carner

hopefully !

Yaya Bey

do it afraid