Trans Musicales has a reputation as a bastion of the unknown - and sadly, that's where most of its lineup is staying.

Very few towns do Christmas as effectively as Rennes. Outside the Mairie a sprawl of tents are full of Christmas foods, their thick, gloopy smell alone threatening to clog arteries. Craftsmen pummel white-hot iron, rending it into gift-ready keepsakes while boys with drooping cigarettes take turns to borrow the mallets, trying to impress a cluster of bored-looking girls by out-mongering the ironmongers. Further into town tiny nativity scenes appear in the windows of buildings so many hundreds of years old that they seem taken directly from an Uderzo panel, exposed beams tilting inexorably towards collapse.

At least, that’s the nice bit of town. Away from the precarious-looking timber, Rennes actually looks quite a lot like Woking. There’s lots of cheap concrete, none of which has weathered particularly well, arranged in a series of slight variations on the theme of ‘oblong’. It’s as if the council has decided to see what happens when it combines ‘Brittany postcard-perfect’ with ‘British Rotary Club wasteland’.

Brittany, the north-western province of which Rennes is the capital, is considered to be one of the Celtic nations – meaning, ostensibly, that it shares at least as strong a link with Cornwall as it does with Paris. Both have an unflaggingly optimistic independence movement, but while Cornish secessionism is characterised by a (perfectly reasonable) hatred for Jamie Oliver and second homes, Breton nationalism seems to revolve around singing. Or, rather, shouting. On the bus from Transmusicales’ swish daytime venue out to the freight airport in which the evening shows are held, Brittany’s youth is in full voice. In the doorways of the three-carriage vehicle underage lads with crew cuts bellow the anthems of their region while cadging each other’s joints, swigging whiskey, and mournfully chewing on baggies long emptied of their crystally contents. We ask a efficiently-refreshed girl opposite what the lyrics mean. “It really doesn’t matter,” she cheerfully replies.

Logistically, Transmusicales bears comparisons with Sonar. The daytime programme is presented in a swanky new venue in the centre of town, in a boxy room fitted with a stunning soundsystem and absolutely no character, while the evening events are held in a freight airport just outside town.

Now in its 34th instalment, Transmusicales is still programmed by one man. Jean-Louis Brossard has been all but singlehandedly responsible for the festival’s lineup since 1979, and in that time he has accreted the halo-esque aura of one with some mystical power of divination. To its very great credit, Transmusicales seems to sell out not on the strength of the headliners but on the promise of exciting new acts, and Brossard is to thank for this.

This year, though, the halo seems as if it is beginning to slip. There are murmurs of discontent about the higher profile bookings during the evening sessions, with popstep prodigy Madeon attracting particular ire. (And reasonably so; while inoffensively fun on record, his set grates quickly and painfully, consisting entirely of cheesy buildups, crushingly predictable drops, and right hands raised at the appropriate moments. His visuals are the most interesting element of his show; it seems that the final remnants of futurism can be found in the projections behind Madeon’s head – CAD-esque constructions in neon, future-relics from some inhuman next-world.) And yet, if anything, this demonstrates how unique Transmusicales really is. Despite its headliners, the festival remains a bastion for the unknown. And sadly, little of this year’s lineup deserves to be anything but.

Of the hundred-odd acts on the ‘official’ bill (many more appear at Bar en Trans, a fringe event held in bars around the city), very few warrant particular attention. The vast majority are aping near-forgotten tropes of the mid 2000s – or, in the case of the utterly execrable China Rats, just aping the Arctic Monkeys. Of the few, though, there are genuine highlights, most of which occur in the colossal Hall 4; a huge, boxy hangar into which has been inserted a big set of bleachers and an even bigger sound system. Hall 4 becomes the club room, the haze of dry ice eventually melding with the vague amphetamine fug hanging just above the crowd. The sound in the room is genuinely stunning, courtesy of a perfectly installed system that is testament to the festival’s sky-high production values. It is TNGHT that gives that soundsystem its most comprehensive workout. The duo, consisting of Hudson Mohawke and Lunice, make the sort exo-trap that is virtually undanceable and yet utterly gripping; an impertinent clatter that revels in its own presumptuousness. The best four minutes of the weekend come near the end of their set, with the phenomenal ‘Easy Easy’ – a chaotic tissue of shattering glass, second line snares, and elastic vocal samples that seem to emerge from the ground, reaching like Slinkies towards some neon heaven.

Hall 4 also plays host to Maya Jane Coles, who rounds off an extraordinary year in celebratory fashion. The gradient of the Londoner’s trajectory during 2012 was startling; a remarkable rise that saw her responsible for a fantastic DJ-KiCKS and some of the summer’s most enjoyable sets. Here she demonstrates her grip on the very deepest frequencies on the house spectrum, consistently resisting the easy build-and-release urge embraced by so many of her peers in favour of a rewardingly abstruse, gauzy selection.

A handful of gems are also to be found in the smaller rooms. Canada’s Hot Panda are easily the most exciting guitar band of the weekend, wrenching forth serrated, atonal tracks that immediately bring to mind In Utero (indeed they cover a couple of Nirvana tracks in the middle of their set, the frontman explaining in French that they were the first things he learnt to play on guitar while visiting his exchange partner). Their most recent album Go Outside was one of the year’s overlooked treasures, but it is live that they really show their worth.

In fact the Canadian contingent put in a good showing, with Doldrums also proving one of the festival highlights. The juvenile-voiced songwriter is in an unusually restrained mood (at last year’s Great Escape he spent relatively little time actually onstage, preferring to clamber up the venue’s joists), but his comparative dourness mean that the songs are thrown into sharper relief – delicious little wonky things that manage to imperceptibly transgress the boundaries of pop, simultaneously novel and familiar.

All is not well, however, during the days. Held mainly in Liberte, a shiny new arts centre in the centre of town, the daytime shows have the air of a doomed perambulation around memory cul-de-sac. The lineup is full of acts replicating dull things that happened seven years ago. The degree of similitude to never-that-cool-in-the-first-place bands is really staggering, reaching its zenith with acts like Pegase (nice-looking boys with nice-looking instruments who sound like U2 slowed down) and The Octopus (sideburned boys with expensive amps who sound like Jet, and who make quite the most deplorable sound I’ve heard in some months). There are moments of interest, but they are never fully realised. Alphabet are fascinatingly flawed, merging startling multi-part vocal harmonies with satisfyingly chuggy guitars but ultimately sounding a bit sub-Mansun, while We Are Van Peebles unashamedly channel Mclusky, offering a delightfully rough-hewn counterpoint to the ubiquitous synth-shimmer but never quite holding it together enough to really hold the attention.

It’s all quite dispiriting, and not just because of the rip-offs. Instead, the most unsettling theme of the daytime shows is a seemingly wilful attempt amongst the bands to rid their music of any real dynamic. There is no rise and fall, no wax and wane. There are very few melodies either. Instead it is all about affect; as if most of the acts on the bill have looked at British and American bands from the mid-2000s, identified the emotion that their music was intended to elicit (the non-specific melancholy endured by sensitive young men with sufficient disposable incomes and parents who coat their homes in Farrow & Ball), and attempted to create a content-less wash that produces the same outcome. Needless to say it fails on every front, without exception.

It’s a shame, because with the right lineup Transmusicales could very easily recapture its sheen. First, though, it needs to finish its nostalgia trip. It is time, perhaps, for Brossard to start sharing the burden of booking.

- Alfie Templeman previews second album with new single, "Hello Lonely"

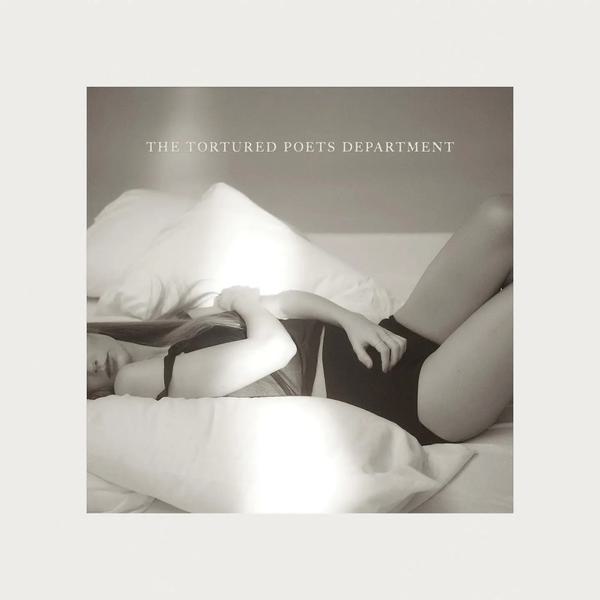

- Stevie Nicks has written a poem on Taylor Swift’s The Tortured Poets Department

- Nas announces Illmatic 30th anniversary UK headline tour

- David Byrne unveils his cover of Paramore's "Hard Times"

- FOCUS Wales Festival unveils full film programme for 2024

- HONNE return with new single, "Imaginary"

- K-Trap announces his forthcoming debut album, "SMILE?"

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Taylor Swift

The Tortured Poets Department

Chanel Beads

Your Day Will Come

Lucy Rose

This Ain't The Way You Go Out